I: Data, Cities

When we analyze cities through the lens of data and maps, how and when do people enter the picture?

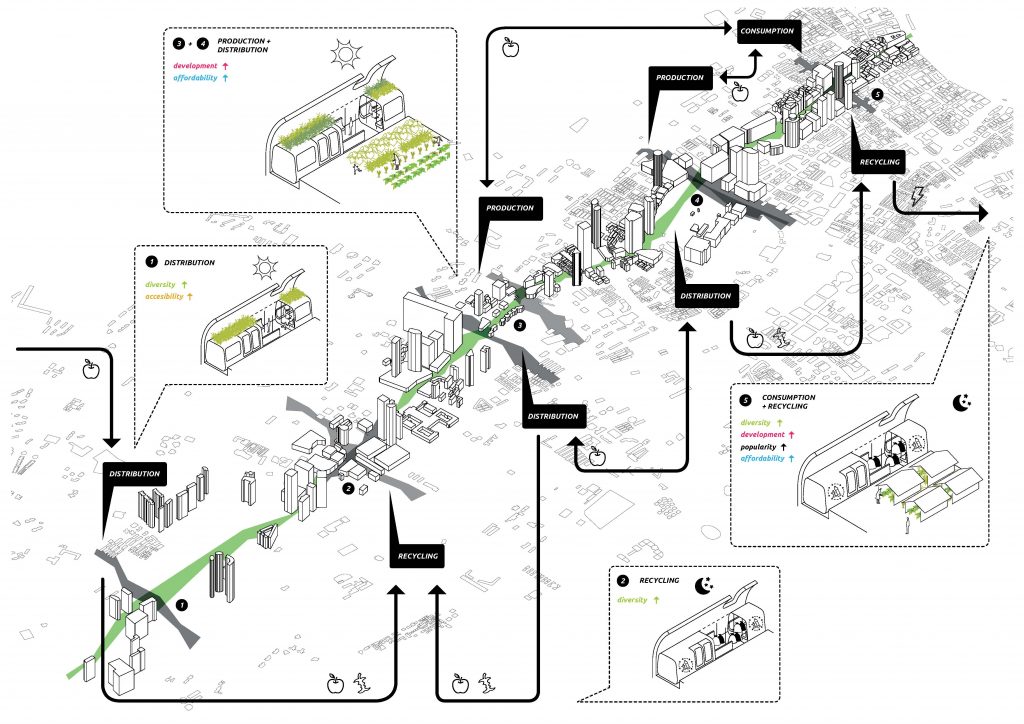

Data City, our data analysis and mapping seminar in the Master in City & Technology, was meant to explore the production, transport, consumption, and disposal of food at an urban scale, through the lens of data analytics. Our professors, Pablo Martinez and Mar Santamaria of 300,000km/s, believe very strongly in this method of analysis, and to drive their philosophy they felt it necessary to steer us away from a natural tendency for architects: to design things, to manifest things physically. Several times, including on day one and during the final review, they said that the course strives to remain in a formless state because there is no single way to physically describe a city. Any attempt to do so is inevitably oversimplified. This fact has haunted architecture and urbanism for at least the last century and a half. As Jane Jacobs says: “There is no logic that can be superimposed on the city; people make it, and it is to them, not buildings, that we must fit our plans.” This statement reminds architects that their influence is far smaller than they imagine; that cities are highly complex ecosystems manifesting the lives of millions of individuals. The Situationists of the 60s also helped to de-formalize the image of the city. Matteo Casaburi, discusses their impact in Architecture + Urbanism: “The Naked City [map]… expresses the incompatibility of Cartesian logic with the real experience of the city.” Even in the important postwar fields of traffic & mobility, the standard method of measuring vehicular flow at intersections with a simple sensor or counter is too minuscule to have a strong impact alone. Researchers at MIT have found real-life applications for traffic flow analysis, but those applications have to remain specific and event-based (responding to citywide emergencies such as natural disasters). Even into the 80s, when big data started playing an influential role, analysts found it necessary to simplify and distill numbers into something digestible. The “Big Mac Index”, for example, uses the cost of a fast food staple as an economic benchmark.

Antti Vuorela, via Wikimedia Commons, license CC BY-SA 3.0.

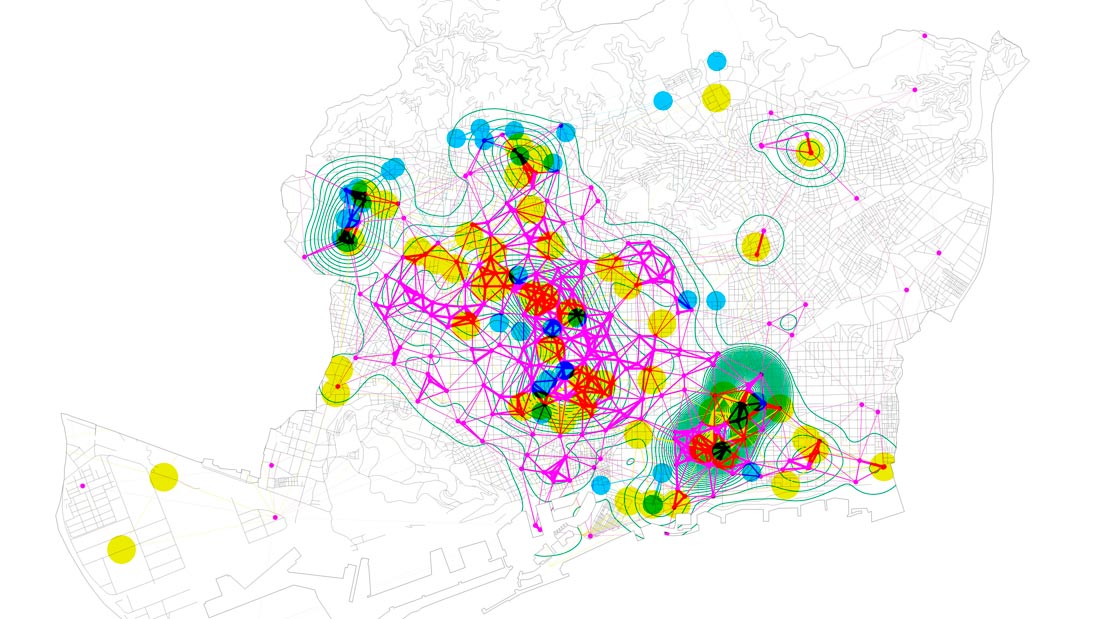

Mapping, on the other hand, can comfortably overlap both the physical and the invisible realms. A strong map can bring together processes, vectors, statistics, territories, buildings, and traffic patterns in one image. It comes closer to painting the full picture because it is more densely packed with information. The Data City seminar took this philosophy to heart. Coming, for the most part, from architecture, we took on the challenge of representing phenomena whose language we didn’t speak. We became willing to admit what we didn’t know.

During the final review, however, the guest jurors inevitably became confused by the multitude of maps and charts on the wall and said, “This is a class about food, but I don’t even see any images of food!” But, as I just mentioned, trying to hopscotch from urban patterns to food items will inevitably frustrate. However, this critique slowly sharpened over the course of the discussion, as naturally happens when people have some time to think about the present work, and by the third time it was brought up, it had matured.

II: Codes, Recipes

Troy Innocent, visiting UI/UX resident at IAAC, spoke. “Why not focus on something specific in the human-scale food experience, like a hamburger or a pork bun, take the recipe for that food, and see how you could affect the food experience by adjusting the variables of that recipe?

Troy had made a profound connection without realizing it. When most people learn about coding, the first analogy that teachers use to demystify coding is cooking. Imagine a code as a recipe, they say, it’s just a set of instructions, and anyone who can read the recipe can reproduce more or less the same food.

The other point in the analogy is that of ingredients. One can adjust individual ingredients and customize the food as they desire. Add salt to taste. Substitute coconut oil for vegetable oil. Don’t have tomatoes? Use mushrooms instead…. Slowly, by adjusting enough ingredients, one can arrive at a different food entirely. That is the approach that Pablo and Mar use in their practice. They use a collection of indicators (like median income, cost of a loaf of bread, distance to transport, average age…) to identify unique regions in a city. One region is distinct from another because at least one of the indicators changes significantly. Then, by the same logic, one can see how changing that same indicator in one region could transform its identity. An “innovation district” could become a “cultural magnet,” or a “cultural magnet” could become an “academic enclave” with subtle changes.

There’s our in. To take this class to the next level, we should look at something like a hamburger or a pork bun, break it down into its ingredients, then see how we could adjust the the recipe by adjusting one of the ingredients. For example: if Shanghai really wants to promote food sustainability, then it needs to reduce the carbon output of its agriculture, and if one were to reduce the carbon output of its rice fields, then the taste or cost of a bowl of rice might change. This would connect the city-scale mapping-scale analysis that we did with the personal, cultural dimension that was missing in the final presentation. It would also force us to acknowledge that like in most closed systems, there is always a loss to balance every gain, and we must be conscious of those impacts.

III: Low Heat, Long Time

I went home that day a little under the cava and made it to Lidl just in time to buy groceries, including more cava. As I entered the apartment, with its crusty walls and bathroom tiles aglow in leftover sunset beams, I remembered Ashraf.

He is tall and lanky– his limbs are in constant motion, from his oscillating head down to his goosestep. When he speaks his hands unfurl like kelp stalks, or clumps of earthworms, or as if he’s about to pull an ace out of his sleeve. I had never seen anyone so clumsy move so smoothly. Even when he first walked into my apartment two hours after being scammed by an Airbnb host, and six hours after setting foot outside India for the first time, he was smiling. As he told me his story, as he asked me if he could pray in the living room until he found a mosque, he was smiling. It began as a nervous, uncertain smile. We bonded over football, our admiration for both Lionel Messi and Cristiano Ronaldo (something I found easier than expected given that we were in Barcelona), the transfer gossip, the managerial drama, and the coming World Cup. He was doing his best at pulling off the magic trick of adulthood– it was almost as if he were mocking it, mocking the care with which we all handle our bodies, the gravity with which we carry ourselves, and the burdensome mortaring, like cooking and cleaning, that we toil over every day.

For the first week of our cohabitation, he kept surprising me. One day he asked “So, Ivan, can you teach me how to cook?”

I stared at him. “But what about all that masala your mother brought you? I thought you knew.”

“No, she just packed that. I don’t know how to use it.”

So I showed him. From the beginning. I filled a pot with water, and set it on the stove. High heat, short time. When it started to boil I threw in some soft grains and turned the power down to minimum. Low heat, long time. Those are the basic variables of cooking. Heat and time. And they are usually in balance, like any closed system. More of one means less of the other. We fried eggs– heat the oil, which gets really hot, then throw the egg on. Short time. We made rice– throw everything in and heat, cover, and let sit. Long time.

I had never taught cooking before. Normally one starts with ingredients, tools, techniques, and recipes. But for Ashraf– for us– even that was too much to begin with. We broke the process down even further. I hope my newfound affinity for coding helped.

In the end Ashraf never quite “took up” cooking like one would expect, accepting its indispensability like one does when one moves out to go to college. It’d be more accurate to say he tried it, like skydiving. But his beard grew out, he started wearing contacts, his smile became knowing and mischievous, he started teasing and messing with people. One time he pretended to be hypnotized by Francois at a party, and everyone believed it, because they saw Ashraf as gullible. Only I knew he was mocking his former self. After the party, Ashraf sent me a text message: “You were the only one who was totally unconvinced. I should get more professional I guess. But don’t tell anyone Francois wants to fool everyone longer.” If I could describe his sense of humor now, I would say low heat, long time.