Developers build houses and call them “homes.” They build socially sterile subdivisions and call them “communities.” It’s called “warming the product.” It’s also happening with alleged third places. Officials of a popular coffeehouse chain often claim that their establishments are third places, but they aren’t.

Roy Oldenburg, Introduction to Celebrating the Third Place: Inspiring Stories About the “Great Good Places” at the Heart of Our Communities, 2002

In Celebrating The Third Place, Roy Oldenburg profiles 19 exemplary “third places” across the United States. These are places other than home and work that bring people together and foster social connections. Of those in the book, 7 are coffee shops, more than any other type of establishment. Once I realized this I groaned, since coffee shops have come to represent the default third place for millennials (my groan was partially for shame as well, since I clocked many hours in them in the 2010s myself). It started with Starbucks’ expansion in the 1990s and has since matured into a downright harbinger of gentrification. And its latest evolution, Blank Street, stands out in the post-covid era because of their sudden ubiquity but also because of what may be revealed if you investigate their presentation a little closer.

Blank Street markets itself as an empty table inviting you to sit down for a while, a bench with room for two strangers. It eschews symbolic logos or intricate color palettes in favor of minimalism. This aesthetic was perhaps a convenient outgrowth of their financial model– one of reduced footprints and no-frills preparation to reduce operating expenses– but it has come to also encapsulate their attitude toward the places in which they set up shop. To me, that attitude is a lazy attempt at building a third place. Blankness is not an aesthetic approach any more than an empty bench is a community. It’s saying: “Here, you do the community building part, we are just the backdrop.” That’s just as bad as a developer including a “community space” on the ground floor of a new mixed-use high-rise without any notion of what that space could be used for or who the tenant could be. It’s exactly what Roy Oldenburg describes. Blank Street’s Montague Street location in Brooklyn Heights doesn’t even have real plants behind its glass storefront– as if that were part of its cost-saving ethos.

Taking a cue from “color blindness,” especially the way Michelle Alexander defines the term in The New Jim Crow, I’ll call this attitude “community-blindness.” It’s prejudice disguised as agnosticism, letting the fate of others be decided by things like “markets” or “merit” or anything that allows embedded inequities to naturally play out, while giving oneself plausible deniability.

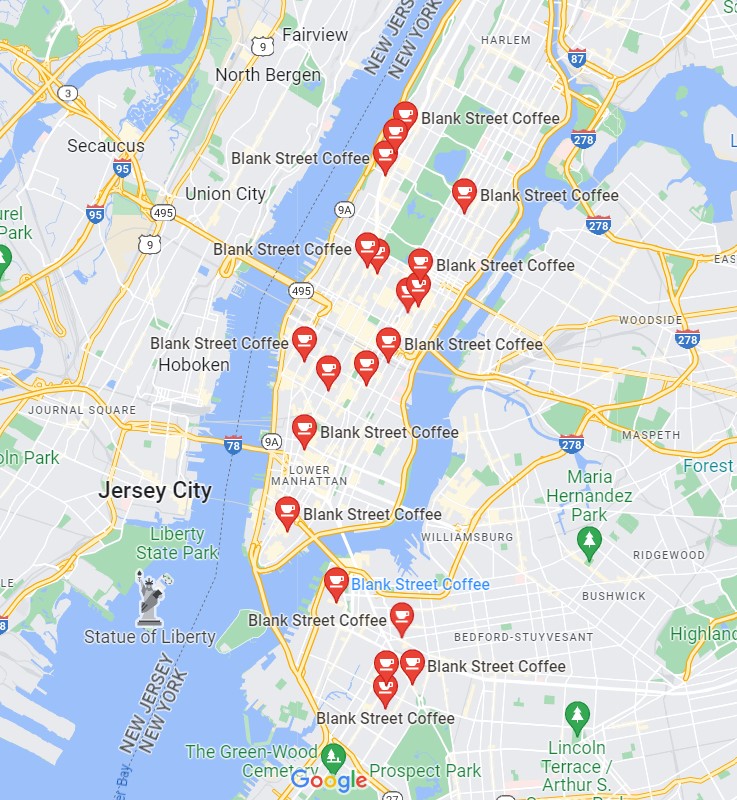

Another glaring piece of evidence of community-blindness is location. Why are most Blank Streets in Midtown and wealthier parts of the city? If you’re trying to make truly affordable coffee and partner with local businesses that need it, why not try opening one in Jackson Heights? Sunset Park? Longwood? East Harlem?

Lastly, in their rookie years, have Blank Street coffee shops really become active community hubs the way they were expected to be? Speaking purely anecdotally, I have not observed the type of messy evidence that a space is being actively used, like the social equivalent of scuffmarks on your shoes. They remain sterile. The way Blank Street cuts down on costs is by cutting down on store square footage and amenities. With that goes space to gather. I’m not saying we need to necessarily go back to seas of tables filled with folks on their laptops (not exactly a bustling social space either) but give neighbors a reason to linger. Forge meaningful relationships with existing businesses. Invite the local plant shop to spruce up the interior. Arrange live music. Install a leave-one-take-one micro-library. Put up a newspaper rack. Pay an artist for a temporary installation. Make the bathrooms public. If community building matters to you, there are many small gestures you can do to enliven the space without having it all fall under your brand. If Blank Street must exist, and if their goal is to deliver a quality cup of coffee without the bells and whistles, I would rather see just a coffee brand named Blank Street being served inside a convenience store or light industrial roastery. I would like Ali, the proprietor of the corner deli, or Jess, the clerk at Lassen & Hennings, heck, even Ashley & Gauthier of L’Appartement 4F (a place I once suspected until I saw their tireless engagement of the neighborhood beyond croissants), to collaborate with you. Save your costs by leaning on your neighbors. And don’t think “if I build it, they will come” is enough– when the community comes, what are you offering them?