My gut feeling is that, like me, when you first learned about Ebenezer Howard and The Garden City, you fell in love.

England at the turn of the 20th century was living a double life. For centuries it had been defined by the characteristic rolling green hills and the shepherds and farmers who populated it. But it was also the cradle of the Industrial Revolution, and all the fire, brimstone, grime, and soot that goes with it. How can one reconcile the productivity and squalor of city living with the majesty and health of the countryside?

Ebenezer Howard’s response was The Garden City. It was an abstract, rational plan for a city which segregated country living from urban working. While it makes sense in principle and in diagram, this segregation was The Garden City’s ultimate shortcoming. To say nothing of the impossibility of separating human beings from nature in general, people’s lives cannot be stretched out over such vast distances in order to separate their place of dwelling from their place of working.

But the diagram stuck, and the principles are by now folkloric. The Garden City is the quintessential example of a theory that is proven wrong again and again and yet refuses to disappear. Even as recently as the 1960s, Jane Jacobs observes in the introduction to Death and Life of Great American Cities that the urban planners of the day continued to promote Garden City-esque planning practices despite their obsolescence. I think the main reason for this is that the Garden City thesis is so simple and so diagrammatically clear that it seduces a design-minded individual into believing that it can solve a problem as complex as a city.

It begins by reducing all of the activities and functions within cities down to a handful of generalized categories (such as residence, industry, and commerce), and then these categories are each given a monolithic section of the city plan on which to exist. Intermingling and gerrymandering of these categories is strongly discouraged, and the more geometric the territories, the better.

This is the basic idea of Zoning. While the typical city zoning regulation is more complex and nuanced than this (for example, it doesn’t care about how geometric a zone is, or how whether multiple zones overlap or intermingle), it is only so by a degree or two of magnitude.

But, to fully appreciate the influence that The Garden City has had on planning, look no further than one of the last half-century’s most successful computer game franchises: Sim City. Will Wright, the game’s creator, must have jumped for joy when he first read about Ebenezer Howard. The Garden City, in its deceptive simplicity, practically anticipated city simulation video games. The two are mere steps apart.

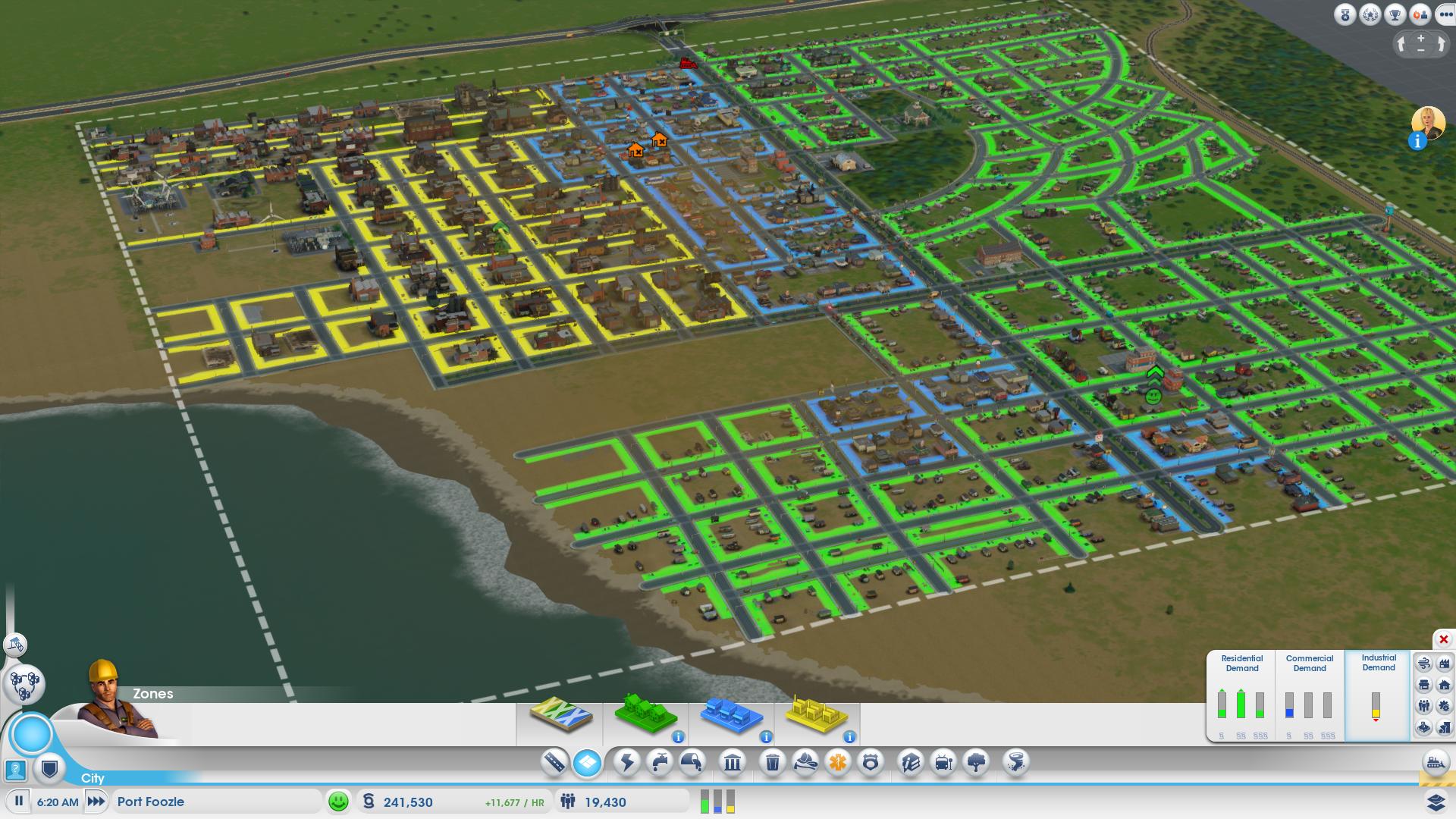

Throughout its many versions, Sim City remains the same: the player is the Mayor of a city, and needs to grow it. How to grow it? He or she lays out designated “zones” (one of three: green residential, blue commercial, or yellow industrial), connects infrastructure (water, electricity), provides public services (schools, police stations), protects from natural disasters, and manages the city’s finances. I can’t praise this game enough for its merits AS A GAME– it forces the player to manage many moving parts at once, and the fact that it has no real “levels” to “beat” makes for endless gameplay hours. That being said, as a template for actual city planning, it falls into the same trap that Jane Jacobs accuses her contemporary planners of falling into: oversimplification.

The simple truth we may have to admit is that city planning conducted by an individual designer (or for that matter even a superteam team of designers) is futile.

Cities have long ago grown so complex that no single person can accurately plan their growth. There’s a clear paradox: how can something which is a part of a much larger system properly comprehend that system? How can a cog be expected to run a factory? How can an ant be expected to build an anthill? It’s unreasonable, and should not be expected.

Could this same claim be made, parenthetically, for individual buildings even? Are they also too complex to be fully comprehended by a single person? Perhaps, only if that person is meant to be the sole inhabitant and user of the building. Otherwise, they are bound to fail as readily as if they were redesigning from scratch the master plan of the City of Los Angeles. I spent a childhood confronting this problem in front of a screen while playing Sim City. I was led to believe that the problems of a city are graspable, summarizable, comprehesible.

Or was that the point of Sim City?

Perhaps I’m thinking about this backwards. Perhaps the lesson there was that citymaking is an endless endeavor– hence, no levels or bosses. I’ve always been drawn to games about exploration, worldbuilding, and inventing your own fun. Put that in the context of a city huffing and puffing before your eyes in isometric birdseye, you begin to understand that you never can MAKE a city– you can only set yourself TO MAKING it.

MolleIndustria has a great write-up with exactly the same takeaway: let’s enjoy the game and its success, but let’s not forget that cities are too complex for one mayor to control. We may be able to nudge, we may be able to react, but we will probably never be able to control.

Jane Jacobs acknowledges this difficulty in Death and Life, and treads carefully and with great detail into her recommendations for city planning. She advocates for things like “diversity,” which at first seems too abstract to yield anything concrete. But that may be the point– city planning, as well as worldbuilding, may need guidelines that sit at the edge of concreteness, that require us, the inhabitants, to define them and make them real.

One reply on “The Ghost of Ebenezer Howard”

Now there is a far richer city planning game called Cities: Skylines. I recommend checking it out. Of course, it is limited, as any simulation must be, but a vibrant modding community has applied expertise from numerous fields to enhance the simulation in various ways. In the video linked below, a thoughtful player (YouTube user Yuttho) showcases some aspects of his city while discussing walkability with city planner/urban designer/writer Jeff Speck. Yuttho’s whole series of videos about city planning (in Cities: Skylines) is imaginative, educational, and (to me, at least) delightful. https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLy_Vsb-9ZWP4KJ2yvwuE8gV-JJljsUcwI