Architects thrive in the jack-of-all-trades role. We fantasize about being great designers, and great builders, and great theoreticians, and great teachers, and great dressers…. But, of course, consummating a union of all aspects of building is difficult to achieve consistently on every single project, particularly the theoretician part, particularly still in the early years when recognition and craft are still developing. Imagine a 22-year-old Bachelor of Architecture, fresh into his or her first job after school, working on stair details for a high-rise or bathroom vanities for an apartment renovation. Staring at those drawings, the mind of a young architect becomes the stage for a duel between:

In the red corner: the polished theories, styles, and techniques he or she was learning just a year ago in school, and

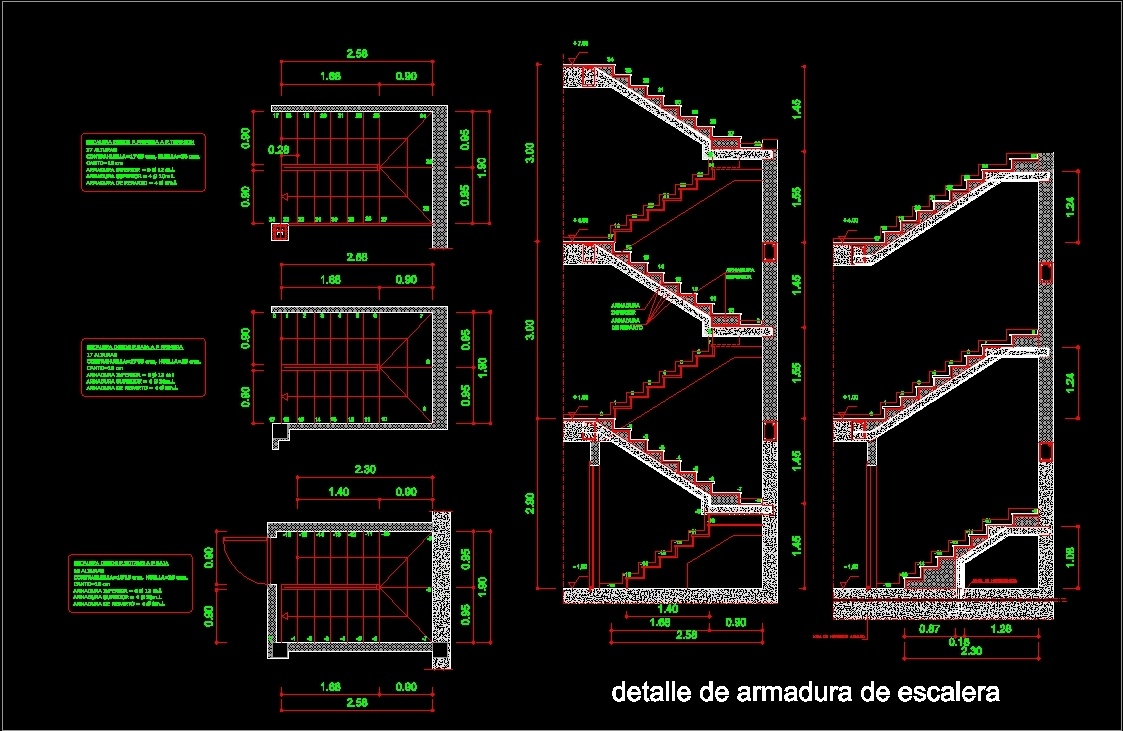

In the blue corner: the tiny, insignificant detail currently underneath the AutoCAD crosshairs, and this 6PM deadline.

The young architect thinks to him- or herself: “How theoretical can I realistically be on a $10,000 kitchen renovation? How much philosophical & spiritual weight can I expect a single cabinet to carry? How aligned with the cosmos can a stair nosing detail really be? And even if I achieve it, how can I be sure that the world will perceive it?”

The nitty-gritty reality sets in. Deadlines. Budgets. Other people, with other theories. Eventually, the majority of architecture projects run out of time or money or will on the path to perfection, and the result is, from the architect’s point of view, a discounted version of what they were imagining. This tug of war is omnipresent. Sometimes a project needs to get done in spite of the idea or spirit not being consummate (for political reasons, for money, for preserving your relationships, for preserving your own sanity). Other times, there are projects that are worth pursuing and prolonging because of the appeal of their ideas or spirits, even in the face of un-recoup-able costs or burnt bridges.

Good practice (that is, functional and sustainable practice) most often ends up being neither too theoretically stifling, nor too pragmatically brash. If an architect can calibrate their expectations just right, they might achieve an alchemy, where a building or detail which satisfies all parties, falls at or under budget, gets built on time, and strengthens the interpersonal relationships, also can embody some higher ideal in its form.

For me, if that alchemy can be achieved (and it can, as you’ll see in the examples below), the most critical moment is the moment of creation. That is, the moment when an idea acquires its first physical form that is perceivable to the senses. That the built environment is indispensable to humans by now makes that creation necessary. One cannot fantasize about providing shelter– one must actually make it at some point. In that necessary creation can be found a grain of truth: The best way to measure an idea is to rub it up against physical things. An architectural theory cannot be wholly measured based on its relation to other theories– it must be brought forth through experiences. Kant made this very clear. So that internal conflict felt by every young architect, though discouraging, is actually a reaffirmation of one of architecture’s virtues as an art form– it brings the best out of ideas and materials by forcing the two to interact. God is in the details, right? Architecture, as it appears to someone, should contain somewhere in its form the spirit which birthed it, or at least traces of the struggle that spirit underwent to survive. An observer should be able to link one to the other…

But this isn’t always true! Sometimes, in the name of creation, a detail is made in spite of that assumed kinship between ideas and materials. Sometimes a building’s form gives “truth & beauty” an unexpected runaround.

What are we to make of Mies Van Der Rohe having the rivets in the Fansworth House foundation piles ground off…?

…or Aalto wrapping the metal columns of the Villa Mairea in wood…?

…or the Ancient Greeks themselves? The reference of wood tectonics in stone (a.k.a. petrification— Heinrich Hubsch was among the first to challenge the common theory that Classical Ancient Greek stone temples were simply stone referencing wood)…

…or the muscular bulge of columns (a.k.a. entasis)…

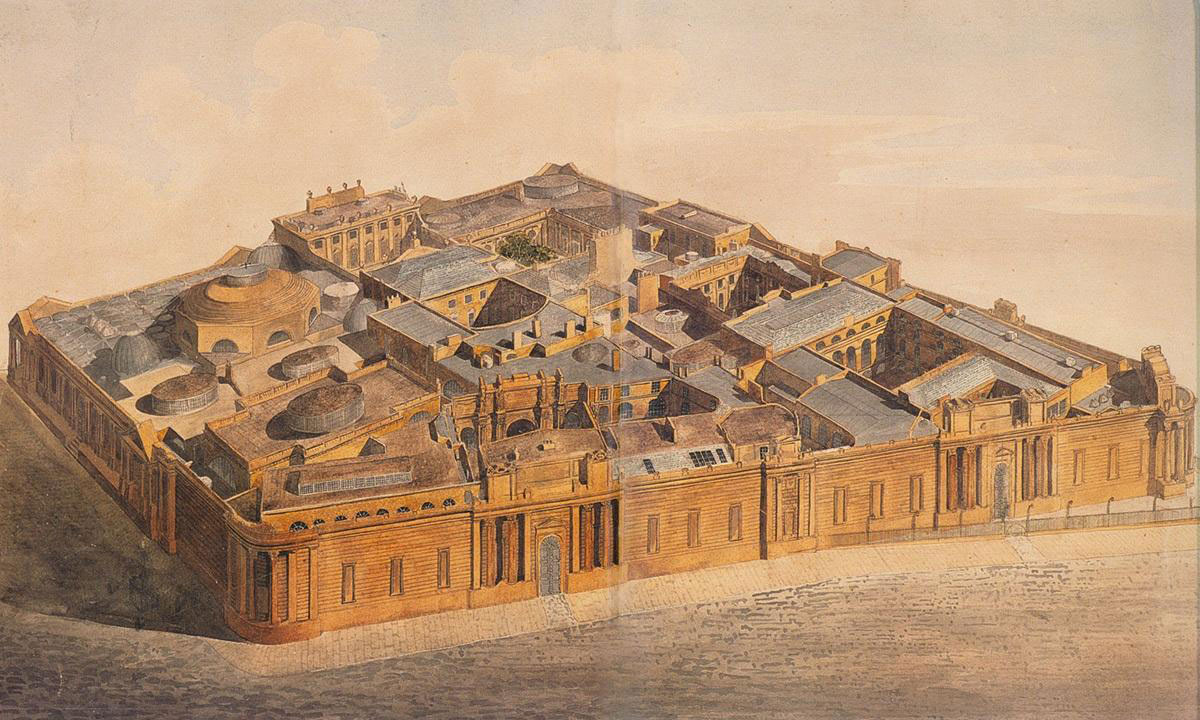

…or, more generally, Joan Soane’s Bank of England? It was one of the first examples of a building divorcing the primordial bond between the expressiveness of the facade & the function of the plan (most notably at the acute Tivoli Corner on the northwest where the rounded colonnade responds more to the bustling street than to the minting happening behind it). Taken in larger context (England’s development of debt, centralized finance, and the speculative market), the Bank of England building is a great distillation of the 19th century’s notorious struggle to reconcile using historical styles for contemporary functions.

All these are examples of detailing against nature, or,(more optimistically) an expansion of natural tectonics through human imagination. It is an idea outmuscling a pragmatic reality. It is a theory outshining a compromise. At times, it is more important, even more theoretically sound, to express something else, something unnatural, something only to be dreamt about.

Ornament is no crime.