There’s little to belittle Bjarke Ingels’ approach to architecture. It fires on all cylinders– through his youth, his energy, his charisma, his Scandinavian origins, and most importantly his ability to make design more accessible to the common man. These are all desirable traits, and thus far his ability to steward positive change on a large scale is inspirational.

But I use the word APPROACH in particular because what deserves a second look is its RESULT (the impact of both the buildings themselves AND the philosophy which birthed them).

Optimism has, to me, always been less about the kinds of thoughts one brews in one’s own mind and more about how one responds to those thoughts. It would be shortchanging to consider optimists as simply those who think nothing but positive thoughts– the key detail is that optimists always consider positive outcomes. They are able to observe and thus initially perceive the same ills and plight as pessimists do– they’re not blind– the difference lay in how they turn those forecasts around, how they refuse to accept what intuition might dictate: that a bleak present implies a bleak future.

If architects are to be civil servants, protectors of nature, engines for change, and collaborative problem-solvers, they must begin with an optimistic attitude– not only because improving the conditions of living is the noblest of all pursuits, but also because such a mindset automatically shifts their motives outward, and acts as a firewall to those hyper-theorists, sculptors with licenses, and ___others who would claim to serve others but seldom look past the end of their own noses.

Another benefit of optimism is that it fuels creative activity. An assuredness or hope that things can be improved more easily leads to taking on a larger workload, and never to refuse a challenge. Yes is more!

Sometimes however, optimistic architects can leave things behind. And I hate to hinge my critique on form and aesthetics, but I think it reveals an important pitfall in that kind of thinking– a pitfall which ultimately works against optimistic architecture’s core principles.

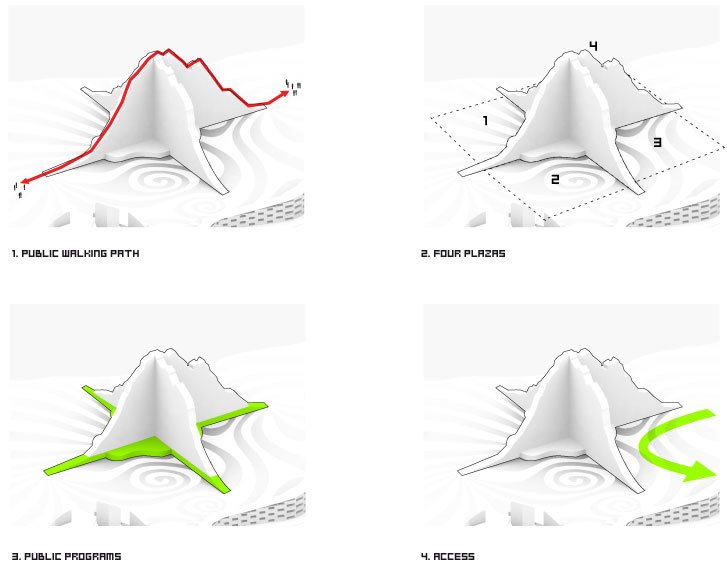

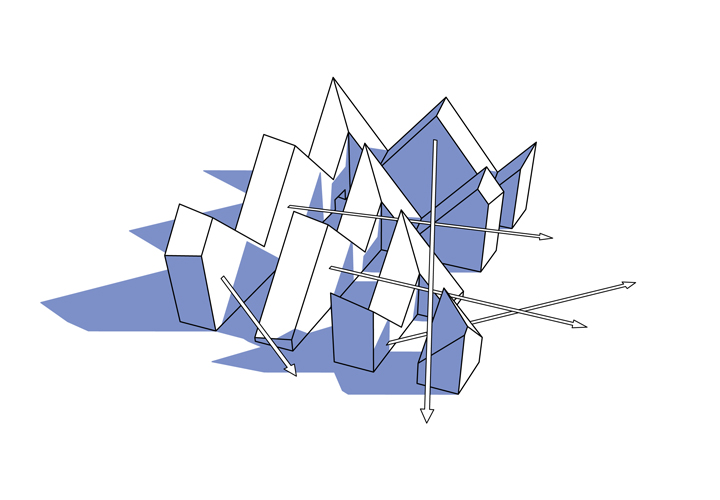

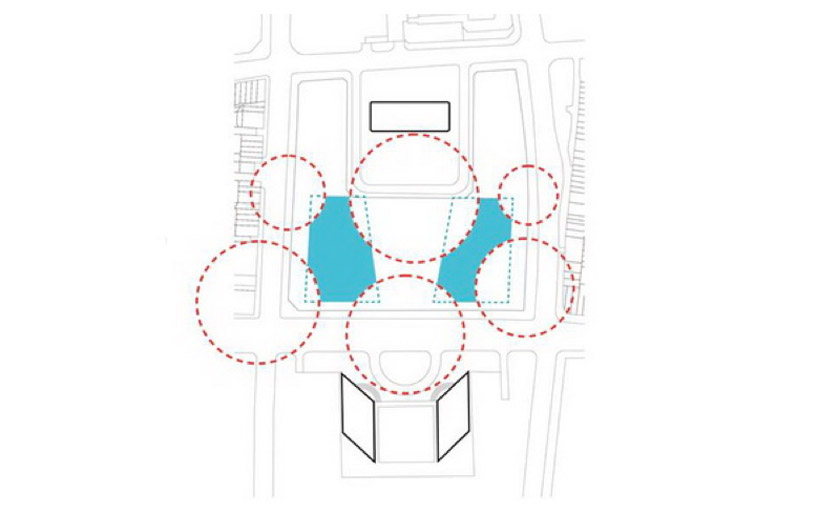

Don’t the projects of BIG, JDS Architects, Ole Scheeren (not surprisingly a protege of Rem Koolhaas– he of the building-that-looks-exactly-like-its-programming-diagram) sometimes appear too formally simple? By simple I mean that the parameters that governed the envelopes are too obvious. You can see this in Bjarke Ingels’ summary of the “courtscraper” building on the West Side in Manhattan (at 19:00 in the TED talk video): solar studies, views, and contextual references are too obvious, too similar to the massing model, and the human-scaled details that residents will encounter on a daily basis haven’t developed yet. The materiality and thus the physical presence of the building is lacking. And yet we’re pulled in by the great renderings. To be true to the level of development of the project, it’s better to show the building as an abstract mass, as if it were 3D printed. Optimism and pragmatism have led to a building that is so correct in addressing all of the specific issues of the site that it doesn’t allow for unexpected material moments to crop up and inspire the kind of contemplation that has sustained great works of art. Again, this is not to say that this materiality couldn’t be achieved with closer design, but I’m seeing a pattern in many larger-scale developments, where a certain glossiness persists: both with regard to the use of scale-less, glossy materials (aluminum, glass, etc) and with regard to a consideration for detail early on.

The end result may be sexy, but the method behind it is as bland and unimaginative as simply visualizing the local zoning regulation in three dimensions, which is something every architect does on every project.

Perhaps this is a function of schematic design (detail is not worth exploring until we sketch out the full mass). Perhaps this is a function of youth. Perhaps it is a function of the split between builders and designers that has gone on since the Middle Ages. But unless this is a paradigm shift in our definition of “the beautiful”, we are simply looking at the sacrifice of beauty and contemplation for the sake of pragmatic optimism in design. We are so dedicated to “solving the problem” that we are letting materiality and craft fall by the wayside. There is a simple reason for the necessity of this sacrifice: the dire global issue of sustainability (in the face of climate change, overpopulation, and resource depletion). It parallels the structural changes that took place at the Bauhaus under Hannes Meyer– the changes that gave the school the machine-made, assembly-line style that laypeople nowadays associate it with, and which in fact was a far cry from the work the school originally produced in the 1920s under Walter Gropius (such as the intricately detailed Sommerfeld House in Berlin).

Could this really be the case? Is architecture and every other public design service being forced its hand by global issues? I would be remiss to promote a return to the era of ‘masters’ of 100 years ago and prior– an era that quickly became modernism, too preoccupied with things like national identity, corporate interests, and technological allegory to design sensibly for the future. Given the genuine motivations of this current crop of architects and planners, I can only carry my trepidation so far. Ultimately, the pragmatism brought on by optimism brought on my climate change must win out for the sake of the preservation of a noble profession. So it is true: I would take oversimplified pragmatism over nuanced modernism. With two hopes:

- That our generation of architects will be able to preserve the ART of building, that is: conceive of buildings which serve humanity with a dose of mystery. I recommend we continue reading Louis Sullivan for that reason– one of his favorite words is “inscrutable.”

- That the pragmatic model will hold up when it is promoted from within cultural regions other than Scandinavia. Will we be able to spread this mindset to places like India, Russia, Mexico, or Liberia?

And, I’ll be a son of a gun, there ALREADY are such architects! These are architects of social immediacy. These are architects as activists.