Though the details I design daily are not on par with those brought to my attention by Christian (with Peter Pennoyer; resplendent in all their curvature, skirting between the Euclidian and the organic, awash with white plaster…) eroticism figures in our discourse enough to warrant a more than cursory investigation of its stake in the architectural domain. Together with words like fetishism and void, eroticism slipped into quotidian use in our lives sometime during the Cooper years, a setting where enough pressure is exerted from without to tacitly discourage elementary exercises like looking words up and breaking them down in simple English. I was thus very pleased when Christian defined eroticism in exactly that fashion for me as the following: treating all form as a reference to or symbol of the human body. The rest of what’s ever been said about it is implicit therein. Immediately I remembered the hundreds of projects that have been explained in corporeal terms:

SKIN (facades & weather protection systems)

LUNGS (courtyards; and on a larger scale, parks, after Japan earthquake circa 1910)

EYES (Windows–to the soul, of course– and symbols of revelation)

DRESS (I believe it was Alice Coltrane who once spoke of buildings in New York as wearing lingerie. Diane Lewis, imploring us to let our designs ‘just lift the skirt up a little’, agrees.)

RIBS (Vaults and slabs)

KNEES (structural braces)

PHALLUS (Its latest expositor, Trump, displaying his big black erect cock standing as a symbol of the profession, of masculinity, of the rape of nature*.)

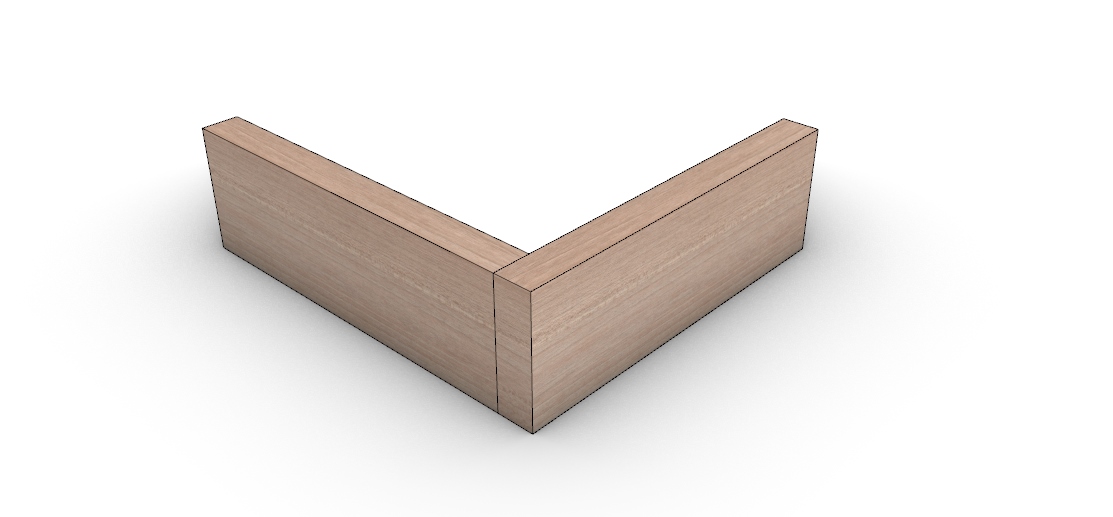

and, of course, BUTT JOINTS

Analogies such as these are common for good reason: they are universally understood. We all have bodies, no? We all spend our entire lives confined to this complex and complicated structure, which allows us to experience many wonderful things but also demands maintenance and care.

(I recall many a critique at my alma mater where professors would wax theoretical about the “body in space.” Now that’s strange, I thought– architects rarely work out, eat crap, drink caffeine and alcohol, smoke, reek (especially in the proximity of deadlines), and spend most of their days staring into screens, immobile in chairs. Who the fuck are architects to talk about “the body in space???”)

But don’t let me forget the use of “eroticism” before architecture became involved in the conversation. The Greek God Eros points us to the big idea: eroticism deals with desire. So how then does desire factor into the design and experience of buildings and spaces? Bernard Tschumi has perhaps expounded upon architectural eroticism most clearly– in Architecture And Disjunction, Part II: eROTicism; pp.70. There, he takes a further step, setting up the direct relationship of architecture to eroticism, both characterized by a duplicity of universal concepts and lived experience. They operate on both levels simultaneously, and are really no different from one another. The practice and the experience of architecture will never lose its appeal to the senses and to the mind, and its ultimate goal which is to give us the space to reflect on ourselves (our desires).

Architecture is also a second womb. Shouldn’t women should be the original architects– all the political and civil rights discussions aside, the one decisive difference between men and women is that women are more pressured to understand their bodies’ cycles and mechanisms– especially in the light of the still-present expectation to be a hard worker, an attractive extrovert, and a tender housekeeper all at once. We have witnessed the role of the architect changing from an actual builder to an orchestrator. By logic, this means that men would perform better as contractors, women better as architects. Hundreds of thousands of years ago, while men were out hunting, women remained at home and cultivated that half of the human physche: the home. I don’t need to repeat what many (most notably Bachelard) have written on. Suffice to say the wilderness and the home are two pillars of humans’ relationships to the world around them. One is through another enveloping body, the other through the enveloping darkness.

The fact is unavoidable that sex will always play a part in architecture by its association with desire and pleasure. When we think of the softness of wood or the smoothness of stone there most likely hovers similar associations of softness and smoothness of other human beings in the background. Since we are social creatures, our obsession with that which makes us alike is instinctual– and hence, when we enclose spaces mutually we are finding bodily analogies in those enclosures, almost as a secret means of communication.*

Is eroticism a label for something universal? Or has the invention of the term drawn our attention to this new sandbox where we can play in the space between immediate experience and cultural overtones (now inescapable)?

It made sense for the 60s and 70s to pursue whimsy and make room for the irrational and unexpected to thrive, after the world realized that the clean-cut undecorated modernism of decades prior could not surmount its puritanical and unsentimental first impression. But it is strange that we strive to find the metaphor (sometimes, audaciously, the simile) for the human body in our buildings considering how different they are.

Architectural symbolism is a brand of out of body experience. They are not just visceral or lucid, symbolism plays a significant role in the interpretation of architectural elements– the end result being an ability to perhaps see humans as actually succeeding in bringing substance to their delusions of grandeur. In matters concerning the divine, which we must admit is a human invention, this grandeur is precisely the goal. Churches used to be educational tools, not just of narratives but also of sensations. Rod Knox can give an entire seminar on the pointed arch (its generator the vesica, a stylized vagina), and the ensuing analogy of entering the kingdom of heaven through (Notre Dame) The Virgin Mary herself.

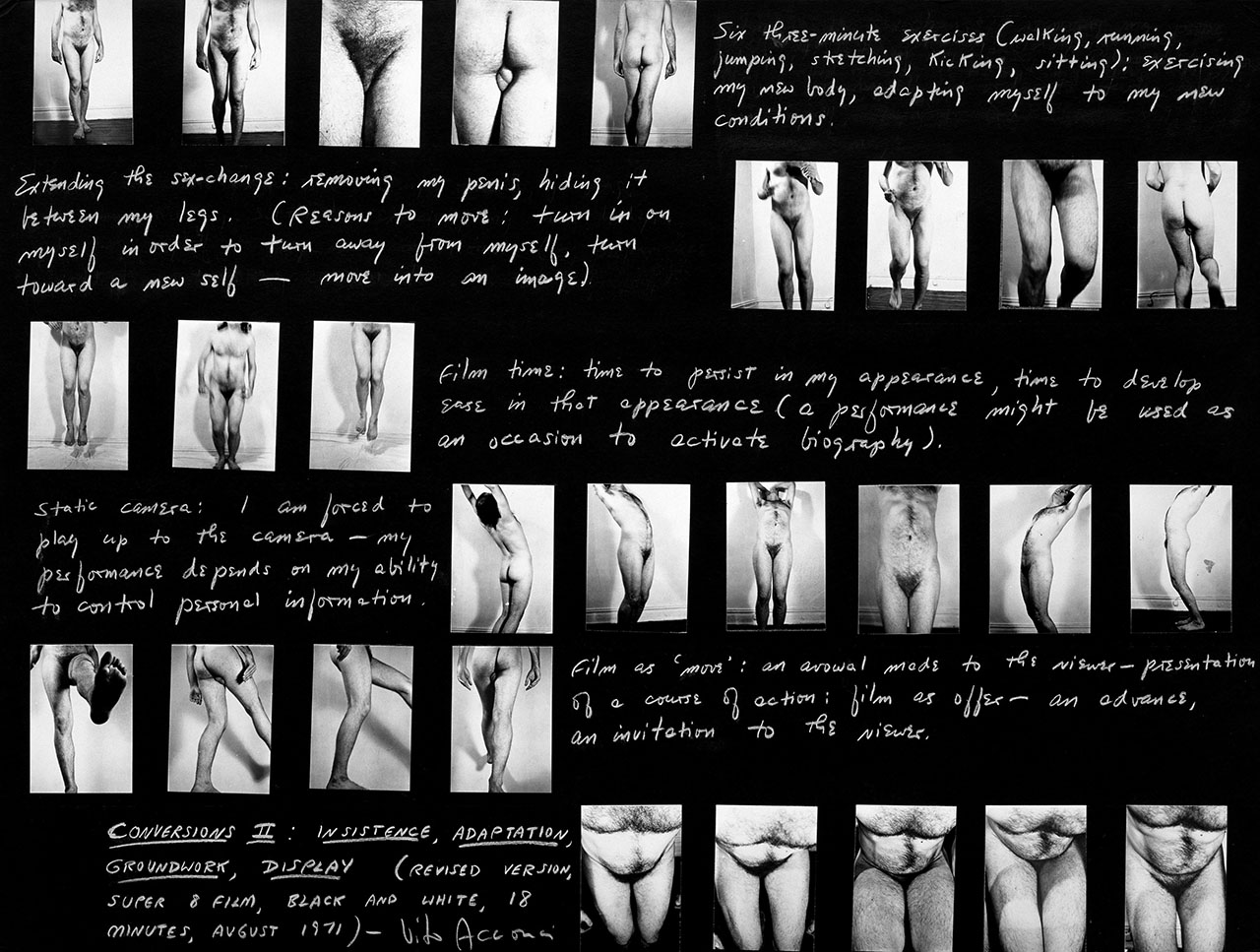

For builders, the body used to be the primary tool. Not just in the sense of digging, bricklaying, and sawing, but also as a measuring device. The Vitruvian Man says it all. So do the imperial units (inches, feet, yards). The body was the generator of perfect proportions which were considered objectively beautiful. That is, not open to polemics and debate. Since then, the body has become the servant, particularly in light of industrialization. One of Marx’s lasting notions describes every object around us as something produced by the capitalist mode of production– that is, the tandem of material and labor. Space itself has recently joined this category, which has frightening implications itself. In this light, each and every object acquires a history and a genesis which can be traced back to our bodies– this time as a whole (“the human body”). Then in the 20th century the modernists, withdrawn and relying on Marx’s definition of products to objectify the body, started to frame it anew as a machine in itself (unsurprisingly, WWII saw the birth of cybernetics). Following the second world war, however, the seeds of a separation were planted. Beneath the new steel and glass skyscrapers, artists began realizing the body as a tragically fragile thing, and something which it turns out is holy to almost all people. The desire then arose to push these buttons, and to examine the emotions associated with the invasion of the territory of the “self”, of the boundary between me and the rest of the world. The body could be manipulated, cut, burned, painted on (Klein), fragmented, as a helpless toy in the hands of a ravenous toddler. The unstylized, and its inescapable ugliness, became the new standard. And as one feared, it slipped to the extreme, a state where being in one’s own skin is no longer comfortable. From built-up anxiety and this sense of separation came a brief explosion in protest (the 1968 Paris riots), after which the body slipped further into culture’s dark cavities wherein the rejects lay in refuge. The raw work that emerged from there (Mapplethorpe, Acconci, to name just two) still carries on today, albeit with a more playful nature. We are neurotic, we are unfocused, we are fragile, we are molecules. There is an attempt, through the illusion of life and thought and feeling, to usurp the previous age’s overwhelming backdrop and bring things that we find nice back to the generating board.

It also comes down often to the continuous desire and drive to build things. It’s of course what separates architecture from design. Jody Brown’s quip on the matter. I was irked by the responses, fanfaring the original definition of “architect” (which I do not argue with in principle, except for when it’s being fanfared) and failing to acknowledge Jody Brown’s real qualm: does something have value before it’s built? Of course it does! Like any powerful ideas, ideas about building can have profound effects. Philosophically speaking, and under the magnifying glass of a profession so slow, it is impossible to build something– nay, do anything, without thinking about it first. I fall into the well-grooved middle road as usual. But it’s true and is worth repeating: architecture must always strive to be built, but mustn’t sacrifice the power of the imagination in order to get there. It is seldom the fault of the architect if an idea doesn’t get built. Does that mean that a then-yet-to-be-formed notion gets completely sapped of its value instantly? As Louis Kahn’s memorial on Roosevelt shows, visions are worth preserving. Because, at the very least, who knows? They may yet see new life come their time. The desire must always be there to affect change in the world on a scale, ironically, larger than oneself. It is an odd and vicarious pleasure, but one that may motivate the design and construction of large-scale projects more than any other.

The responsibility of architecture, as far as eroticism and living bodies are concerned, is to address the immediate, because this is what bodies respond to: the feel of stone, the chill of a breeze, the antsy irritation when a view is slightly blocked, the smell of wet wood. It seems that the long-lasting effects of lived experience weigh more on the intellect, on reflection and knowledge filtered (necessarily) through time– but there are pure and delightful movements that occur in the gut of audience members witnessing a great performance (McCoy Tyner on My Favorite Things, John Coltrane listening reverently aside; the ending of City Lights; MLK’s, Whitney Houston’s, and Dylan Thomas’ voices…) that architecture should certainly aspire to. Not only because it broadens the experience of it to the immediate, performative realm, fostering empathy and establishing a standard of positivity for all people, but also because it loosens the grasp held upon it by the realm of the visual. All thinkers, from Nietzsche to Pallasmaa, have long called for this liberation. It is one of the more erotic exercises around.

*Architecture, like sex, is a violent act. There is nothing redeemable in digging a hole in the earth and sticking something foreign inside, to the detriment of the former. It is hard to see a time when architecture, and the building profession as a whole, was or ever will be fully harmless.

The manipulation of nature (psychologically and physically) is the linchpin of homo sapiens’ separation from it. The psychological manipulation begins with the word “why” and the physical begins with architecture. Perhaps a hypothesis such as the following may be posited: