Skylines are a speculator’s dream. Strictly speaking, they are not real things. In the same way that edges are not really there, but merely the points at which an object leaves a beholder’s eye, a city’s skyline is an imagined contour. If I ask you to imagine New York City’s skyline, you will most likely picture a silhouette with the few telltale icons bristling among generic rectangles. Whenever Related Companies’ CEO Jeff Blau promotes Hudson Yards on the news, he is sure to mention is the development’s contribution to the skyline. The image can also change depending on where you live—whether you look east from Hoboken, north from Ellis Island, or west from the Long Island Expressway.

This imagined state is also what makes it a useful measuring tool. Since it is capable of accommodating many different viewpoints, and since it changes constantly in response to citymakers’ speculations, a skyline is what I like to call the Aspiration Index of a city. It is a summation of all of the city’s past and future ambitions, an agglomeration of jostling voices into a coherent whole.

So the question arises: who controls the fluxes of this Aspiration Index? Who are the big influencers in that market? In the case of New York City, the answer has been clear for over a century: wealthy players in real estate. Since the skyscraper boom at the end of the 19th century, it has always been up to the oil tycoons and media magnates to determine the shape and color of the city canopy. Ironically, those players rarely leave the city themselves, and the skyline they mold is viewed predominantly by the working classes who live on the outskirts. This contrast is especially striking at night, when the city’s tallest buildings illuminate the dark with an array of colors.

The Empire State Building, a mainstay of the New York City skyline for almost 90 years now, has been outfitted with colorful lights on its crown since the 1960s; and since a lighting upgrade in 1976 has started the tradition of being lit up in different colors every night in reference to holidays or other city-wide events. It has become a pastime for some to look up at the lights after dark and guess what the day’s reference is. Over the years, it has expanded into a reservation system, in which various non-profits can apply to choose a commemorative lighting display for a single night. The spire on One Bryant Park even has its own Twitter feed which advertises the commemorations. However, these commemorations only occur once every several days, meaning that for most days the city lights remain firmly in the hands of the property owners, The Durst Organization.

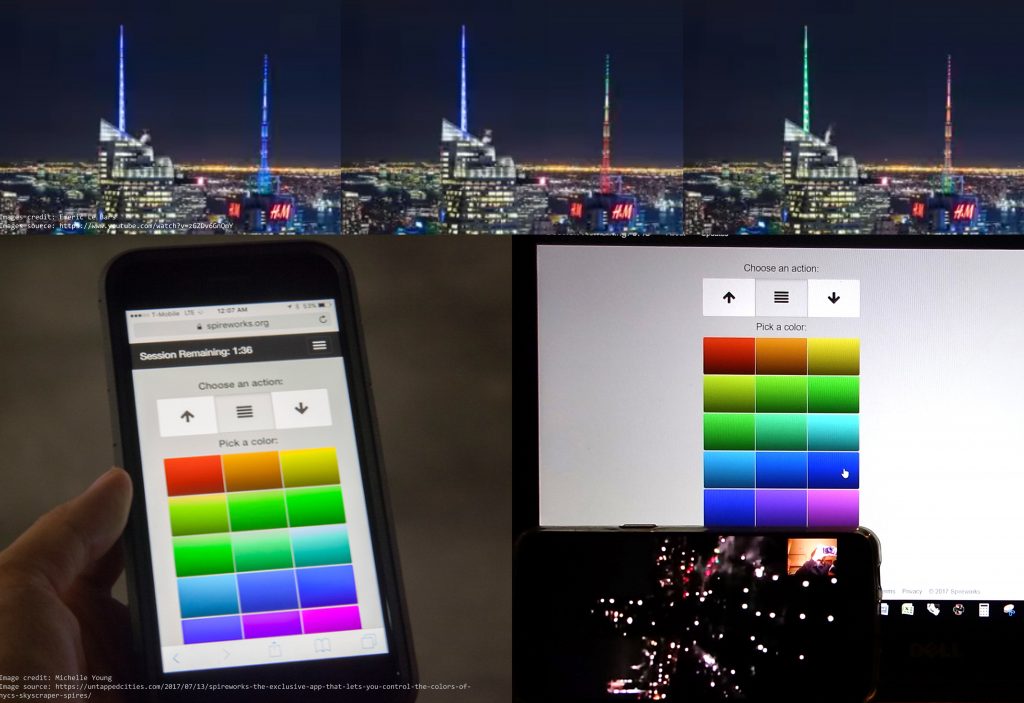

Perhaps it was this detail of the empty, uncommemorated days which gave Mark Domino, son-in-law of The Durst Organization’s Chairman, an idea. He developed an app called Spireworks which allows users to log in and, for a few minutes, control the lights of One Bryant Park in real time. The app was distributed to several thousand users as a test, and it quickly exploded in popularity as users jostled for their chance to send secret messages, impress friends, and seduce dates. For the first time, a landowner had to give up control, and the inhabitants of New York seized the chance to make the skyline theirs. Mark Domino told Metro News in 2017 about his own aspiration to “transform Spireworks into something that has a greater social benefit.”

Admirable as it is, however, it is difficult to imagine what Mark Domino means exactly by “greater social benefit,” beyond reverting One Bryant Park’s spire to an organized, regulated reservation system like the Empire State Building. Meanwhile, since new technology evolves at a pace all its own, Spireworks has taken on a reputation of white-collar exclusivity quite contrary to its original intent. This is partially determined by design: digital queues have maximum wait times so as not to eat up bandwidth, and in order to gain access to the app, you have to be invited by an existing user. Spireworks now gives access to the lights of Four Times Square (also a Durst Organization property) and Domino has stated plans to expand, but that front has quieted.

Less than two years ago I visited my friend in Brooklyn Heights. She took me out on her balcony which faces the Brooklyn Bridge and Lower Manhattan, and said, “Watch this.” She pulled out her phone and began pressing buttons, and in the distance, I watched open-mouthed as the crystal spire changed color within seconds. She sent me the invitation the next morning, but I never touched it. Like the hijacked innocence of the app itself, I never thought of it as more than an exclusive toy. I remembered that day on the balcony when I began putting this piece together, and I called my friend to get a live image. I logged into Spireworks in Barcelona and we opened a Skype call. For five minutes we fidgeted with camera angles and headphones and session timeouts, never quite getting the results we wanted. Maybe there was a concurrent user showing off in Midtown. Maybe the app just doesn’t work from Europe. But there I sat anyway, 3,800 miles away from my hometown, fighting for my momentary lease on the New York City skyline.