For me, there is no better remedy to an uninspiring day than an excursion to the Met. I have been there over fifty times and am still discovering things. I brought my sketchbook– there were architectural thoughts nervously brewing which needed a playful nudge.

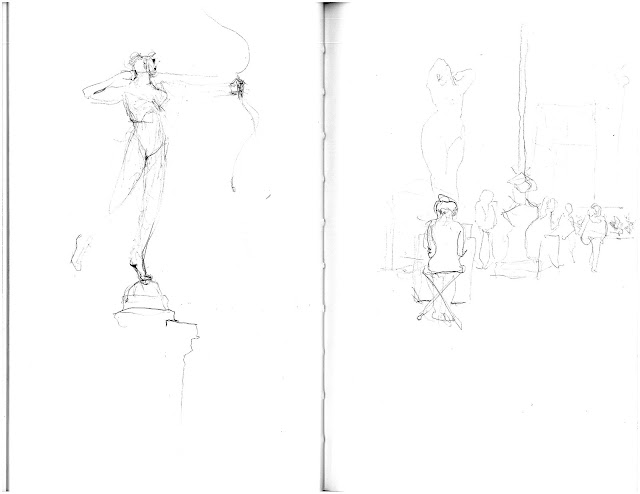

I lucked out, because the Bernini Sculpting in Clay exhibit was just up in the West Wing (the octagon, my favorite Met Wing). For three hours I’d spend my time doing what many masters have done before me; copying the masters.

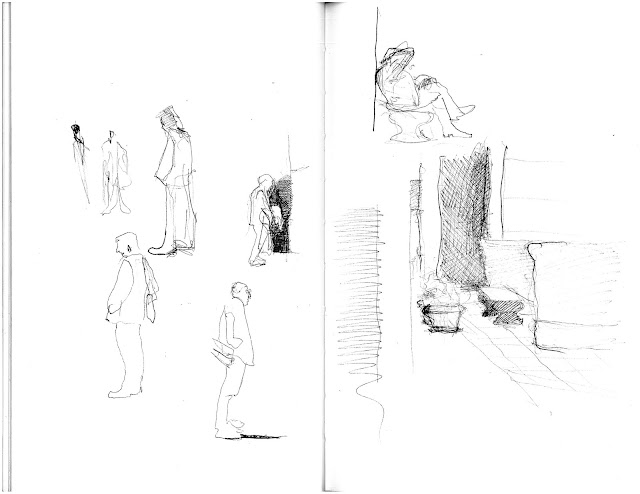

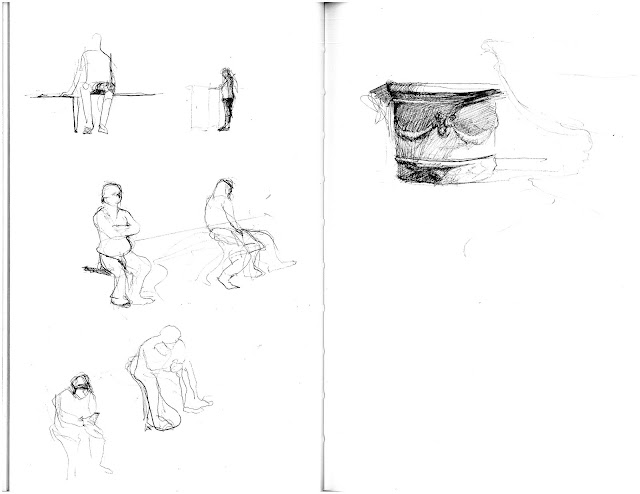

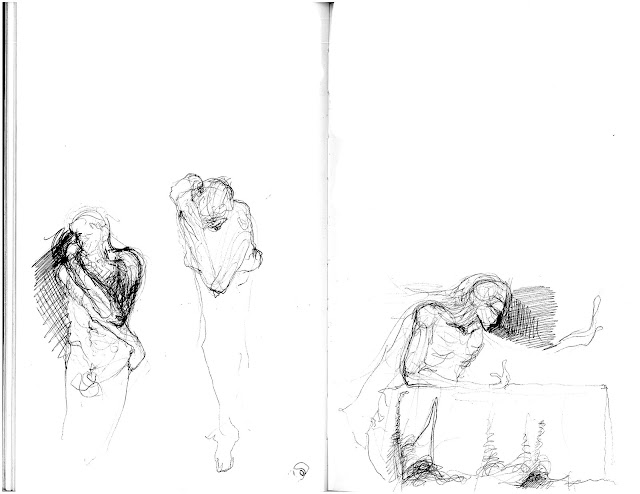

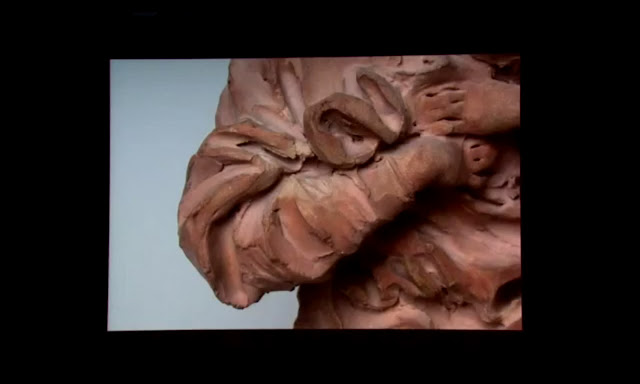

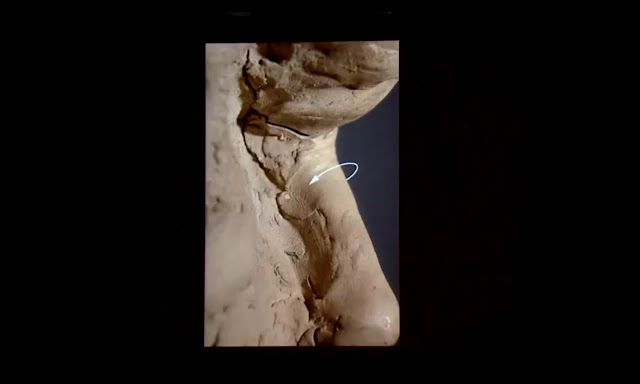

One hour in, I passed his study of a horse. The piece itself was unassuming, little more than a leg emerging from a brick-sized lump of terracotta. What drew my eye away from the piece itself was ironically what opened up the depths of it immediately thereafter. The blurb below it had a photograph attached, illustrating one of Bernini’s common sculpting techniques: starting with a mass in the center, he pulls material away from the center using a circular motion around the axis of the limb. This interested me in three ways: first, in that he begins with the entire mass of clay needed already in place, he simply displaces it using a specific motion; second, that motion is perpendicular to the thrust of that which it is sculpting and hence slightly counterintuitive; and third, and most important, that this rounding-out motion has to happen over and over and over, with great intent behind each stroke, each contributing minutely to the formation of an arm or leg. Like a living lathe this displacement and rounding-out of materials reverted me to a consciousness of drawing which I believed I had exhausted and abandoned years ago. Ever since switching permanently to ballpoint pen (itself largely a decision founded on my reinvigorated interest in writing for which no other pen will do) I began thinking pejoratively of wealth of lines, becoming a convert to clean, singular lines. I thought I was simply channeling the nature of the material, doing what it instructed, like using arches with brick and lintels with wood. But the big con of this kind of drawing is its resistance to displaying process. Oftentimes, a sketch must be worked out as you draw, and for this you need a technique that will allow for gratuity (if you’re skeptical) or multiplicity (if you’re accepting). Bernini helped throw my conception back over half a decade and rediscover the potential for drawing when using that same carving and rounding-out movement in my sketchbook. I felt reinvigorated. I was unafraid of multiplicity of lines, and by extension unafraid of breaking continuity of those lines. There is something deconstructive about adding multiple lines to define a single edge: first of all, it accepts the simple fact that there is no real edge, and second that drawing anything to begin with is a creative and interpretive process, and thus needs to anticipate and accept self-contradiction.

There on in I found myself staring more at the backs of the small sculptures than at the predictable areas such as the face and hands. There, I was trying to discover more evidence of Bernini’s working methods and techniques. And before even arriving at a revelation, any viewer should be greatly taken with the craggy ranges of the clay figures– lumps of clay, the streaks of tools, even fingernail pinches and fingerprints, all loosely coming together, as if frozen in the moment just before collision.

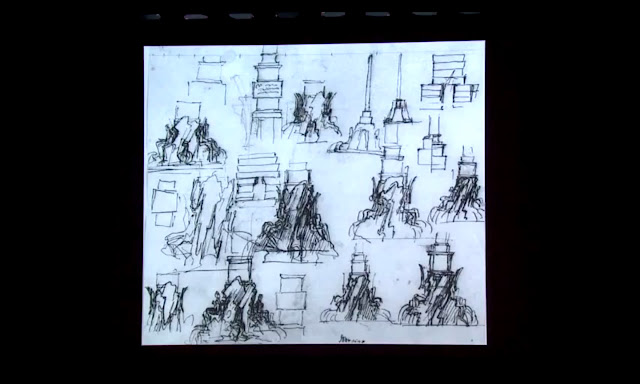

Turns out the curators and conservationists put together a lecture series just before the exhibition opened, the final talk of which I located online. Anthony Sigel’s talk, while half-boring, is a great investigation of Bernini’s techniques and opens up a universe of details. I love Bernini’s own sketches and the x-rays. The exposition made me think of how artists really are forced, as creators, to contemplate and address every single detail– not just the details themselves, but also how they all share space– a single space which ultimately coalesces as an angel, a saint, or a lion.

I realized that the blurbs accompanying every artwork in every museum are just tiny windows into the immense world of art preservation and conservation. If one is to look at that world as complex, intricate, beautiful work in itself, then its initial impression of shallow attempts to definitively explain a masterwork fades away. It becomes a symbiotic world, a world just as concerned with the big questions of “why” and “how” as its reference. Who can deny that for over a century now, every “movement” (artistic, political, technological…) has included within its structure an instrument or a figure whose job it is to record and document it (a stenographer), as opposed to expecting that figure to follow separately afterwards?

A quick search for further information online landed me reliably in the NYTimes. Note the descriptions in the opening and eighth paragraphs: “Everything is in flux, moving swiftly and sometimes violently. Bodies struggle, twisting and turning in different directions…. The clay itself, visibly imprinted by Bernini’s fingers and variously worked with sculpturing tools, seems as alive as the figures it embodies…” That very twisting, contorting, flowing motion is indeed the first impression most are struck with before Bernini’s work– and especially when that work is sketchy by nature: intentionally gestural, quick, and incomplete.

We know we are supposed to solemnly accept the final work as the definitive statement of the artist, bracketed and packaged. We should be able to reap all the information we need from that which we see on the pedestal or in the frame. But oftentimes we are drawn more to the history behind it, the collection of events unintended for display, all that which had to happen in order to create the present work. We come to these events with varying motives (……), and we find in them stories, questions, struggles, perhaps a more intimate inspiration for our own work.

Thus I stood corrected in gallery 955 of the Metropolitan Museum, realizing that my sketches and the Met’s illustrated blurbs were one and the same thing.

Below, bonus from the American Wing.