Frei Otto’s Pritzker Prize win is great news, and a long-deserved recognition. The tensile roof structures for which he is best known are broad and altudinous webs which still knock us on our asses when we see them. Broad, altudinous, and web-like also happens to describe his legacy on the profession fairly well. Here is a brief gaze upon the sweeping web of Otto’s influence.

To begin, some background theory regarding the 20th century’s description of the ether (or time-space, or that infinite continuum of emptiness which matter and energy and the universe and people occupy). The discovery of the elementary particles, the theory that mass and energy are different forms of the same thing, and that space and time exist in an interconnected, interdimensional edifice, were evidence that life, the universe, and everything is quite homogeneous. It was radical to imagine everything we know as simply an aberration of an otherwise perfectly balanced soup… like bubbles in a hot cauldron of star-boullion. OR, according to Gilles Deleuze, folds in space.

Many architects have taken Deleuze’s fold quite literally. Take a look at half of DS+R’s schematic models and you’ll see this intestinal slab worming its way through the section. Take a look at Zaha Hadid’s buildings and you’ll see whitewashed surfaces with little up/down differentiation. Take a look at Frank Gehry’s buildings and you’ll see a career-long attempt at enfolding architecture holistically be reduced to wavy facade treatments concealing traditional construction techniques.

Otto’s work, under brief analysis, shows that it not only touched on these concepts of material homogeneity earlier than the starchitects above, but it penetrated them to the core of architecture. Let Manuel De Landa illustrate. De Landa has long been interested in the overlaps between computer science, genetics, and architecture. As a philosopher he is refreshingly excited about bringing these fields together as great human tools.

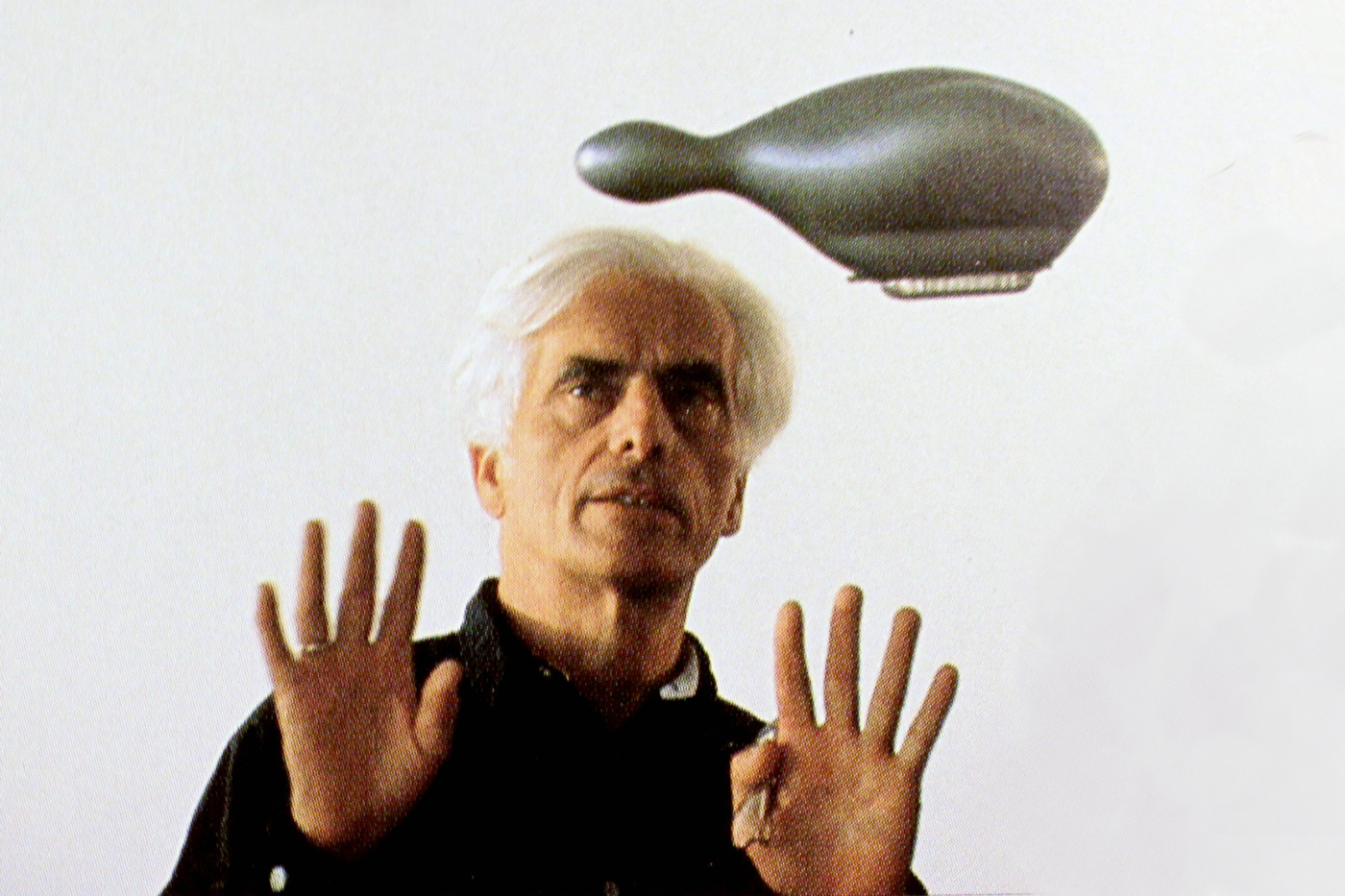

This whole lecture is worth listening to, but at 11:00, De Landa brings up Frei Otto as an example of someone who takes advantage of so-called “morphogenetic pregnancy” in nature. This means: combining the physical properties & limitations of a certain material with a creative designer’s mind to both model reality and build it. Allowing two inherently creative processes to work together, responding to the mutable environment and the consistent natural laws, generates architecture that looks almost like it could’ve been formed without people. The material does its thing– and it acquires a kind of flowing form that begins to speak directly to Deleuze’s fold.

You can think of it as two ends of a scale. On one end is the mind of an artist– a thinking individual with the creative impulse. On the other end is the universe and its governing laws. There exist things that come scarily close to the dead center of that scale: things with an elemental presence, deeply rooted in their physical composition, and yet unmistakably singular, pushing and demonstrating the limits of a particular law or principle as if trying to transcend it.

Examples of this are: the stone arches in Arizona, snowflakes, craters, seashells…………..

……………………….and Frei Otto’s soap bubbles!

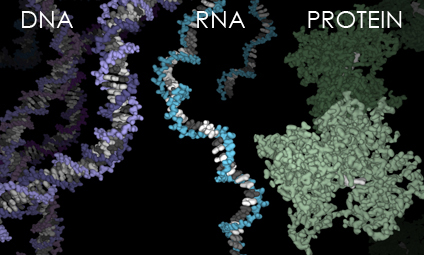

Manuel De Landa argues that, structurally speaking, genetics also belongs to this group.

This is the template for the theory of evolution. More significantly, the 20th century has taught us that the architecture of genetics can be applied to almost every process in the universe– get this, not only in the built environment, or in nature, but in the human mind. And as we inch into the 21st century, we are beginning to realize that every organism, even thinking and feeling are essentially very complex algorithms built of RNA on the same principle as a spreadsheet.

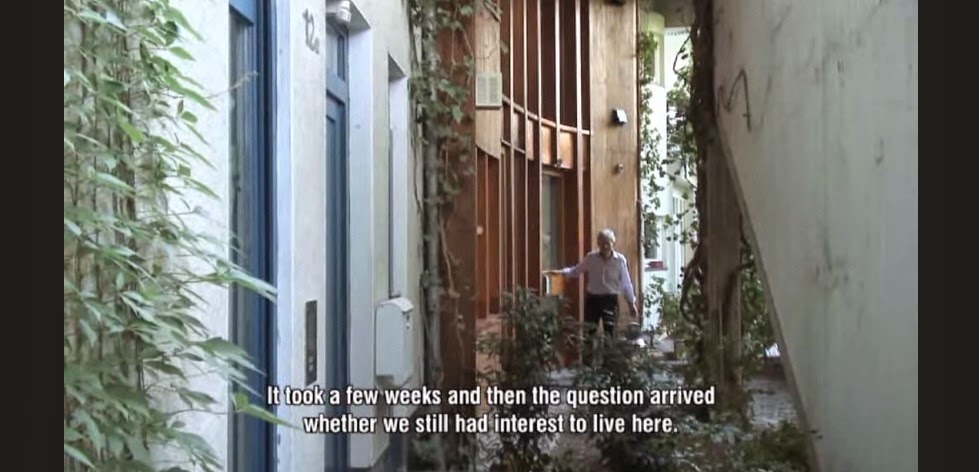

Back to Otto– in spite of what appears to be a rapid dehumanization of the past century, let nobody deny that he felt a connection to or care for humanity, for the empowerment and improvement of the lives of people. His other famous projects demonstrate that he was deeply dedicated to the pleasure of selbst bauen: the control of one’s own built environment (BIY!). However, he didn’t lose sense of the individual’s place within a greater patterned framework, as any successful modular housing needs to be designed. This video demonstrates Otto’s ability to retain the human within the web. Better yet, he made us see that we ourselves are the creators of that web, and that at no scale should the ability to enrich life be ignored.

The aforementioned ennobling of disparate scales is what brings Otto’s legacy full circle. The way he visualized and organized the elements of architecture, tying together in an infinite ladder of relationships, teaches us to look for inspiration for the biggest things in the smallest things, and vice versa (my own photo series microcosmos is based on this inspiration). As a practical matter, 2 things to take away from the Munich Olympics project is that 1) such building is scaleless without reference to the human body, and 2) it works well only as a roof— we are still unable to impregnate architecture’s superstructure, interiors, and systems with that material homogeneity. But we shouldn’t relent in that effort. Can this truly be achieved in architecture, where a single material or single structural pattern makes up every component of a house, rather than wears it like a dress? I believe it can, but the how is a complete unknown. This is not discouraging, this is infinitely motivating. Let’s keep stretching, keep digging, keep blowing bubbles.

Rest in peace, Mr. Otto.