I enjoy academics. They are quintessential nerds, enormously obsessed with miniscule things. The contrast between their enthusiasm and the specificity of the subject is endearing, comical. Watching them interact with those outside their field highlights the contrast, and watching them interact with those inside their field makes me realize that a shared interest alone can sustain a friendship for years. For my part, interacting with them is a unique challenge: either they talk alone to a speechless audience, or they are speechless in the face of small talk. I want to impress them with my general knowledge of trivial subjects while also playing ball with the topic of their thesis, though I sometimes catch myself nodding and laughing at comments I do not understand. They aren’t socially shrewd enough to sense the emptiness in my eyes. I become detached within ten minutes. Melancholy settles in.

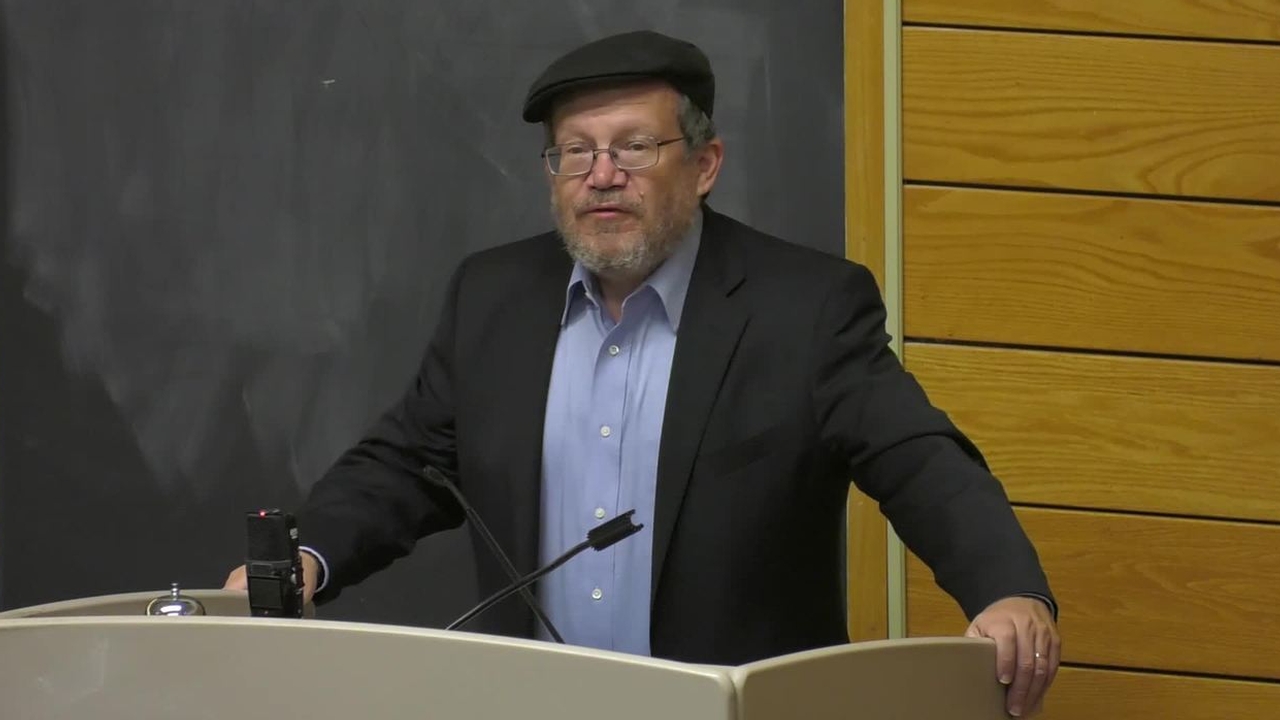

Charlotte hosted a two-day conference recently on the topic of Jewish ghosts, directly related to her own freshly-minted thesis. Any discussion of ghosts and what they signify is sure to shift eventually to themes like collective memory, shared traditions, inheritance, and a host of things the describe the constant negotiation each of us has between ourselves as individuals and ourselves as members of a community. On the top floor of Kent Hall in Columbia’s Morningside Campus, Charlotte introduced Jonathan Boyarin, the keynote speaker. In front of a packed room, he gave a lively, humorous lecture about how death shouldn’t be feared or dreaded, that it doesn’t suck the life out of things. Instead, it can actually inject life and generate thought. During the Q&A a woman asked about something I don’t remember. Boyarin answered with an un-memory (we seriously need a word for that) of his own: that he was teaching a class, whose name he didn’t care to remember, whose goal was to dispel the myth of self-making. The notion that one starts from zero at birth and spends life building oneself up and creating one’s own identity is false. We are not as self-made as we imagine, Boyarin reminds his students; we are as much a product of the traditions and communities we are born into.

After the Q&A we all went to dinner at Talia’s Steakhouse. An upscale kosher steakhouse with white tablecloths, metallic wall paint, and pudgy, gruff waitstaff. In spite of the decorum however, there was a flat-screen TV in the corner. It was showing a baseball game on ESPN. Now, everyone who has spent any time living in the 20th century understands the hypnotic power of a television. Even if you are not into sports, dislike commercials, or stress about the news cycle, you cannot resist staring if there is one on in the room. I have seen the faces of intelligent, anti-consumerist libertarians go blank, sentences stop midway, and eyes turn away from mine to watch a Chevy commercial. So there I was, trying to play ball with successful academics, with a television glowing above their shoulders like a postmodern Sword of Damocles. The restaurant was loud and I sat at the end of a long table. The woman I sat next to spoke endlessly and walled me off by leaning in a lot. My distraction was sealed.

All I remember was: Houston Astros and Washington Nationals. 1-0. I don’t know who was winning. Da Bears.

The academics talked with obvious tones about museums and Jewish history. About the failure of Yad Vashem in Jerusalem. About the fight between the founders of the Tenement Museum and the City of New York. I took one shot at engaging, ad-libbing for a couple of minutes about as many novel topics as I could: classical and country music, gypsies, Finland, and the fascinating relationship between Adolf Hitler and Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim.

Nonplussed silence. They resumed talking about museums. And leaning in. I resumed glancing at the TV.

The camera panned over the field from behind home plate. People were on their feet, holding up phones and spinning t-shirts. Chanting. Embracing. The pitcher camera shook slightly from people jumping up and down in the bleachers. Under the floodlights, the players glistened slightly. Every chance they got, the broadcasters squeezed in a replay from a few innings ago of a solo home run or a slide into third. The excitement was palpable even from where I sat. I thought about sports. How remarkable it is that humans have developed a setting for controlled competition. Essentially: synthetic, defanged war. We have a deeply-rooted desire to witness epic narratives unfolding in front of our eyes. We obsess over the character arcs and plotlines, even if the consequences of those plotlines to little bearing on the rest of our lives. I thought: Even with a low-scoreline, low-consequence, mid-season game like this, people still come out by the thousands.

Our food eventually came, I had to be a good boy. More talk about that question fielded by Professor Boyarin at the lecture: that the American myth of self-made men is false and potentially harmful. We need to acknowledge the role of communities in the formation of our personal, heroic, epic narratives and that we benefit day-in, day-out from the aid of others, even those we do not know.

The following day, I passed by a morning paper on my way to work. The front page photograph showed a glistening group of baseball players rushing the mound against a dark background. “Nationals beat Astros for World Series title.” How easily I forgot about the World Series.