My post on Bernini made me recall a critique in advanced drawing seminar under Sue Gussow. That time she invited a guest professor who identified a simple dichotomy. Looking at my drawings– charcoal on bond on the left, ink wash on mylar on the right– he noted the contrast in technique represented a larger duality, one that happens to bracket the entire history of drawing: that is, the Cartesian style of drawing, and the Euclidian style of drawing.

It was the first time the distinction had been described to me that way.

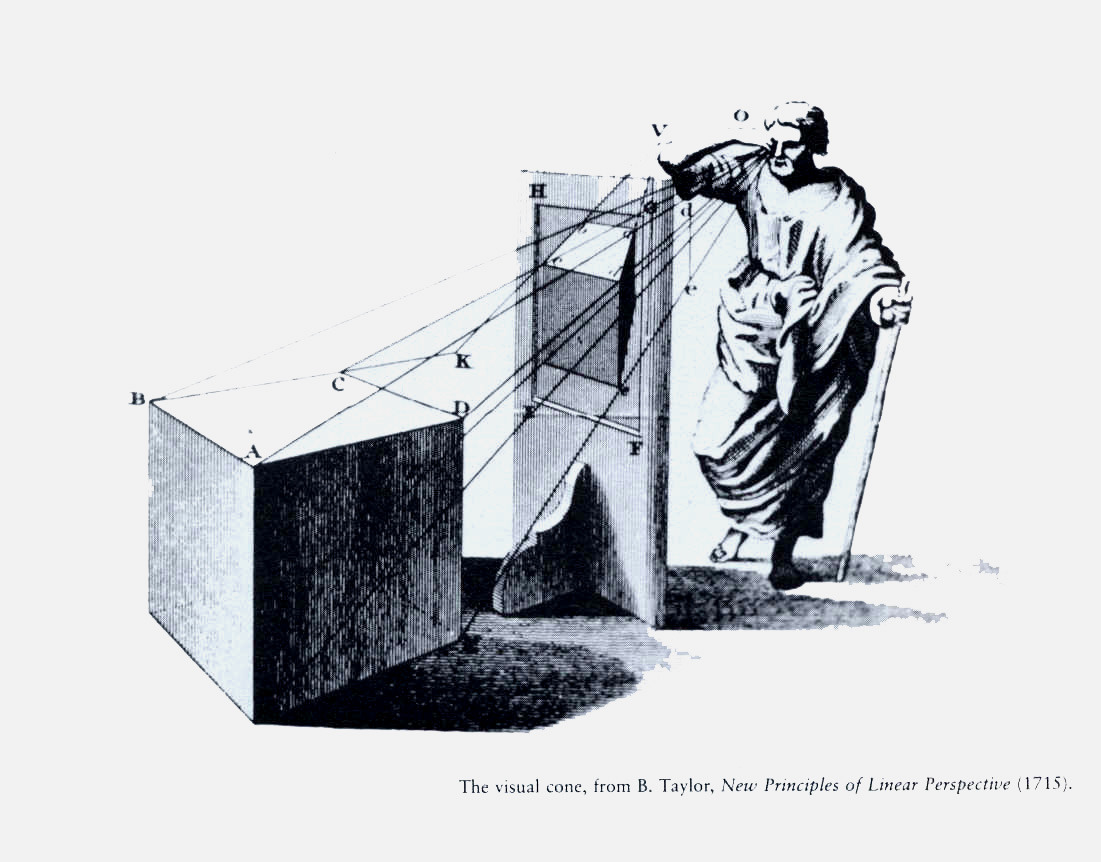

Pencil and pen are archetypes of the former. With thin lines, minimally varied, drawing in the Cartesian style is an exercise in mapping: the delineation of points, borders, edges, lengths– in essence, vectors. The distance between a nude model and a series of 3mm thick lines on bond paper is one of the furthest distances we can achieve in representation– this makes the illusion of mass that much more astounding. The aforementioned points, edges, and borders do not really exist in the world they represent.

Cartesian drawing is the perfect example of applied mathematics. The time when communication with pictures needs to be absolutely clear and unambiguous is the time when those pictures must get mathematically abstracted. Cartesian drawing relies on suppression of how the human eye works: emphasis on numbers, a maximum of one unknown at a time, and proportionality (in the way a mathematical equation is proportioned).

Charcoal sits in between both extremes because it does have a finite girth, but is nonetheless treated as a line… ink on the other hand is a liquid, without a maximum girth or even any constrained form. Instead we impose bottlenecks on it (most commonly the brush, but can also be a fingertip, a quill, a sponge…) after the fact, at the moment of drawing. Architectural drawings are done by and large in the Cartesian manner, in 3 senses: 1) the lines are represent abstract borders between materials, 2) views of a building or element are largely orthographic projections which humans cannot see, and 3) the drawings are not ends in themselves– they only serve as instruction for construction. The advent of autocad further accentuates this vector-based modus operandi– and we the architects unnoticeably grow more and more accustomed to representing space using vectors. It was thus pleasing to the professor in question to witness the attempt to delineate space using a painter’s or sculptor’s sensibility.

Why this division in the first place? From my perspective, it seems to hinge on when, in the course of creation, do we allow for subjectivity? Architecture requires an effort of such coordination (always has) that to anticipate the intersection of labor and materials requires us to establish a relationship where there is a definite answer– in other words, to delay the intoxicating subjectivity. The correctness of that answer only needs to be integral within the system. In the meantime, one suppresses drawing, thinking, and working in the way that our eye and brain may initially suggest– ways which, according to the laws of perspective, are disappointingly egocentric. If multiple people can be expected to create something together, there need to be rules. That’s why we have constitutions. The benefit of working as an individual artist is that of subjectivity: you are expected to be answerable only to your own perception (i.e your own intention).

There’s a strange balance at play here. I don’t want to make the distinction as simple as: surface & mass = egocentric subjectivity, lines & vectors = universal objectivity. Because, after all, how can representing a mass only as light & shadow be subjective when all people perceive this way? Where does the egocentricity come from? Can we not simply trust our fellow humans to be seeing exactly what we’re seeing? If the perception of mass & light is the only norm, then why do we disagree with interpretation of those images?

It is doubtlessly enriching for all architects to attempt to work a priori with surfaces and mass, rather than points and edges. It survives to this day, but only in the necessity for renderings, to represent the architecture to everyone else. By contrast, the Cartesian drawing method is only a large detour on the path to realizing a building. Ultimately, most architects want spaces to communicate using light, mass, texture, and sound– that is, in a Euclidian manner. The Euclidian drawing method should use the same part of the brain that fires when logging perceptions and memories within built environments. It got me thinking: could there be a renaissance in store for Euclidian drawing in the building profession? It would, I think, be more of a renaissance in our own minds– developing or exercising a kind of perception favoring that method– while the technique abides.