Once a year or so, which is as frequently as my pride will concede, an old lesson from a professor pops out of my memory and hits me with a that’s-what-they-were-talking-about! moment.

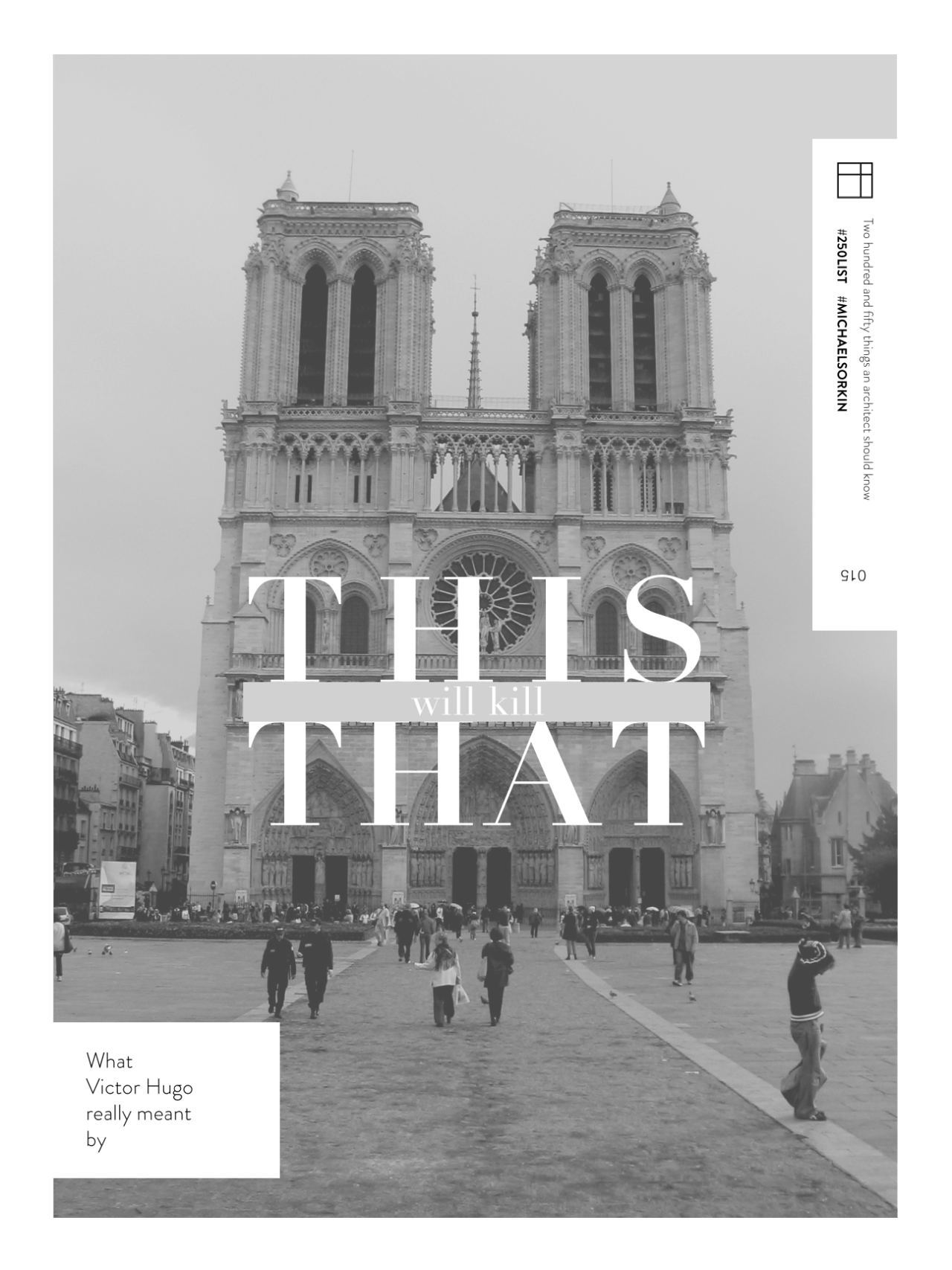

The most recent one came while walking around Paris, the professor was Anthony Vidler, and the lesson was a pantomime of Claude Frollo’s “THIS WILL KILL THAT” line, from Victor Hugo’s 1831 Notre Dame de Paris, on a dull evening in his Modern Architectural Concepts seminar.

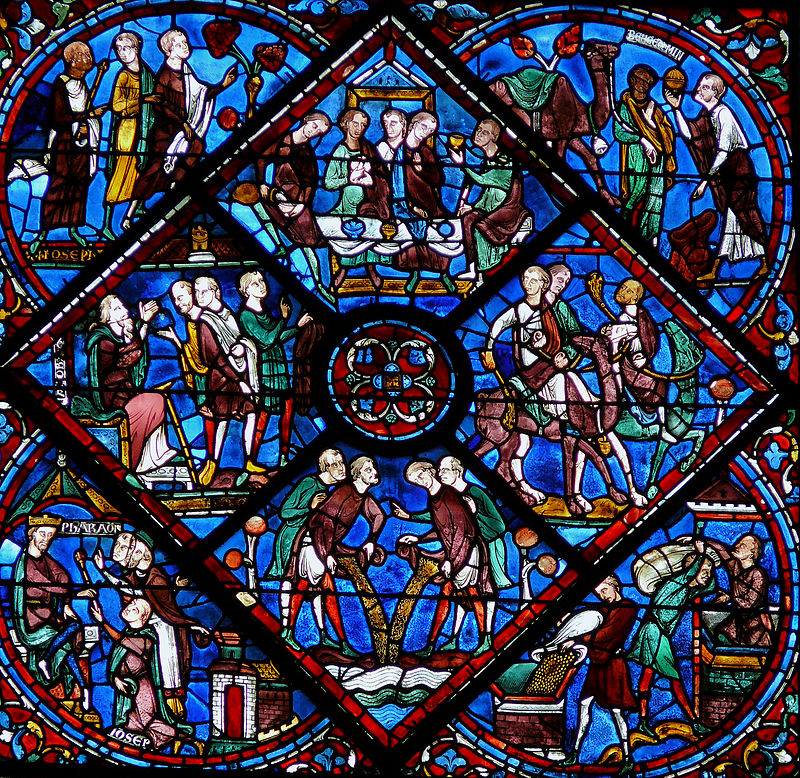

The gist of this moment in the book is the declaration that the printed word will usurp architecture as the prime conveyor of information to the masses. Up to that point, buildings were designed always with the illiterate inhabitant in mind. Through their placement in the city, their facilitation of public assembly, their material connection to the earth, and their ornamentation (gargoyles, friezes, mosaics, stained glass windows), they told a story about themselves and their world. These stories were told in pictures, sculpture, sound, and more. We believe that people were likewise more attuned to these messages when words and written language was not front and center. But then it did become front and center, and architecture lost its need to tell stories in pictures– why bother meticulously crafting a work of art through the collaboration of a stonemason and a painter when you can more easily etch words onto a blank wall? Even further– why bother carving words when you can print them and hand them out as pamphlets at the building entrance?

How fitting is it that such a poignant statement in literature is set in Paris?

Paris is very well-decorated. It is ingrained in the spirit of the city. “How do I make it beautiful?” is a separate but equal question to “How do I build it?” We don’t call it the City of Lights for nothing. But there came a time, in the 20th century, when Paris became so saturated with historic architecture that it became like a huge museum. I imagine myself a contemporary Parisian city planner. For fear of destroying its history, I avoided new additions to the homogeneous urban fabric. I forgot that the very history I was preserving was founded on baroque sensibilities– whimsy, emotion, sparkle, darkness– that prefer volatility over permanence. Worse, I no longer spoke the language of pictorial architecture, so I couldn’t see this plain fact literally carved into the city around me. When I looked up, I saw beautiful containers worth preserving when I should’ve seen living, breathing artworks that are unafraid of death. Unafraid because, unlike me, they know the irony that their historic appearance was due in part to Baron Haussmann’s big urban reset in the mid-19th century, in which many medieval neighborhoods were razed, mid-rise limestone-clad houses with mansard roofs built, and boulevards widened to aerate the public realm.

If I look at it the way Victor Hugo did– that books have killed buildings by sapping them of their beauty– modernism was not a great revolution in architecture, but more like designers grasping for straws, realizing that austere aesthetics are inevitably becoming the status quo, and reactively finding justification for it. But it is harder that it seems to eliminate ornament entirely.

—

I took a morning to visit the Centre Georges Pompidou. The museum was described in the guidebook thus: “by exposing the plumbing, HVAC, and other systems that run the building, the architects put form before function and found the ultimate expression of modern architecture.”

I thought wait wait wait. No one required Piano & Rogers to paint the pipes different colors. Au contraire, the systems were exposed in order to become decorative! The reason Pompidou is a great building is that it goes against the form-before-function tenet of modernism. It recognizes that each building contains thousands of opportunities to add a little humor, whimsy, or emotion to our environment. Like all aesthetically stimulating buildings it speaks multiple languages: light, sculpture, painting, ceramics, metalsmithing, botany, weaving, plumbing, all the details of craftsmen– rather than just architectonics, the English of the built environment. Richness of ornament is tied to richness of spirit. How fitting that such a poignant statement in architecture is set in Paris? Pompidou helps revive the baroque qualities of a city that once made it playful and alive.

This may be the best lesson of post-modernism.