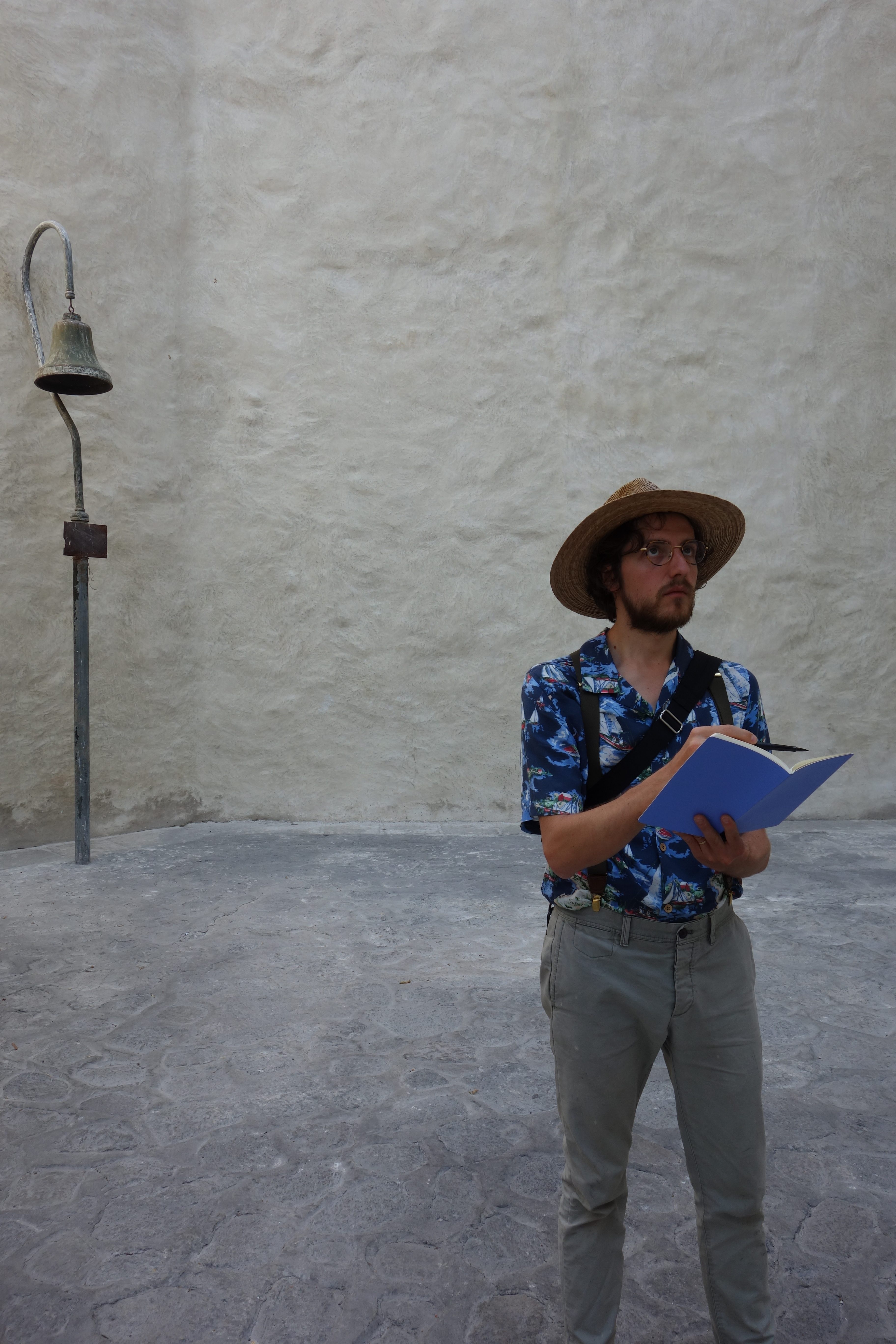

Already some time ago I discovered the joy of observational freehand drawing. Aside from benefiting my mentality (I can count it as meditation) and its use as a learning tool as I observe the physical world, drawing opens channels to engage the people around me. The cold stoicism of modern strangers melts away when they see me drawing, especially when I draw portraits. They approach with curiosity, and often a conversation will start. When a subject sees me drawing them, they immediately fix their posture, smile, and continue what they were doing with a gently glowing pride. Last week in Alameda Central I was drawing celebrities from memory when a meek ten-year-old boy approached me, with two or three of his friends behind him, and complimented my sketches. I said thanks and asked him if he drew. He said he did a little, so I invited him to do one in my sketchbook. It was of Emiliano Zapata. I tore it out and let him keep it—his smile was so broad as he walked off that it touched his friends’ shoulders. Whenever I go to a bar I sketch a portrait of the bartender on the back of the customer receipt (which I never keep) and leave it with the bill. With just a little more effort on my part (surprise, surprise), I can break down barriers!

It didn’t come to me easily. Like many my age, I came to art through photography, which is a younger, more technologically advanced medium (that is to say, it’s much more convenient for the user), but which in contrast carries much more baggage. To begin with, it’s an impersonal gesture to lift a black box to your face, putting it in between you and someone else, blocking the possibility for direct eye contact. We know of the superstition that being photographed is an intrusion onto the soul. This belief is reflected in the baked-in metaphors we use to describe the act: “To take a photograph.” “Sacar una foto.” These verbs imply an extraction from the “real world,” never to be given back. In 2002, the year I took up photography seriously and exchanged my iPhone for a Minolta X-700, I visited Guatemala with my parents. We took a ferry across Lake Atitlán to tiny Panajachel on the north shore, whereupon disembarking we were greeted by a local woman selling souvenirs for quetzales on the dollar. Instead of buying or even responding I raised my camera to take a photo, and immediately she wrapped her free arm around her four-year-old daughter and turned her back to me. In an instant, in front of everyone else on the boat and the villagers on the dock, I had changed the mood from optimistic to sullen. I felt like a bad human being. If it had been ten years later, I would have instead taken out my sketchbook, gotten a smile, a pose, and maybe even a compliment. I could have given the woman 5 quetzales to pose for me for 5 minutes, then I could have sold it to someone for 20.

Though the art establishment (that is, the faction of society that has looked at this from all angles and analyzed it to death) has decreed that neither drawing nor photography have license to the truth, that neither is extracting something from the world any more than the other, there are qualities of the latter that simply don’t sit well with the human intellect. Because our species is so dependent on, indebted to, and entrapped by its sense of sight, it is difficult to convince oneself that a photograph is not a product of our own vision, but something so comparatively rudimentary, so mechanical (with mirrors, chambers, hinges, and electric signals), that the only justification for its existence is the creative impulse. The internal debate rages on between our intellect and our instincts, and it’s our own fault for inventing so deceptive a medium.

Drawing, in the meantime, has for ages remained comfortable in the middle ground where I think art should reside: between reaping a fruit that nature has spent time cultivating on the one hand, and inventing a fruit supplement in the laboratory on the other. I discovered this after paying a man in Central Park to do my mother’s portrait for her birthday. Not only did he do it swiftly and accurately, he then became my teacher. As a matter of fact, I should be grateful to photography, because it has taken over the role of documentation (and the scrutiny that comes with it) for which drawing used to be responsible (the vestiges of which are found, for example, in the portrait etchings in The Wall Street Journal). Where before kings and presidents had to commission a life-sized painting for their official portrait, they can now come into Annie Leibovitz’s studio, pose for 15 minutes, and be done. Humans are much more comfortable encountering something unknown than they are coping with the loss of something they knew.

This is not an indictment of photography—I just had to outline certain problems that it can’t seem to get rid of in order to highlight the ease with which those same problems dissolve with drawing. When all I want to do is record the characters of the world, their bumps and curves, doing so in pen and paper is my E-ZPass around these modern existential complications.

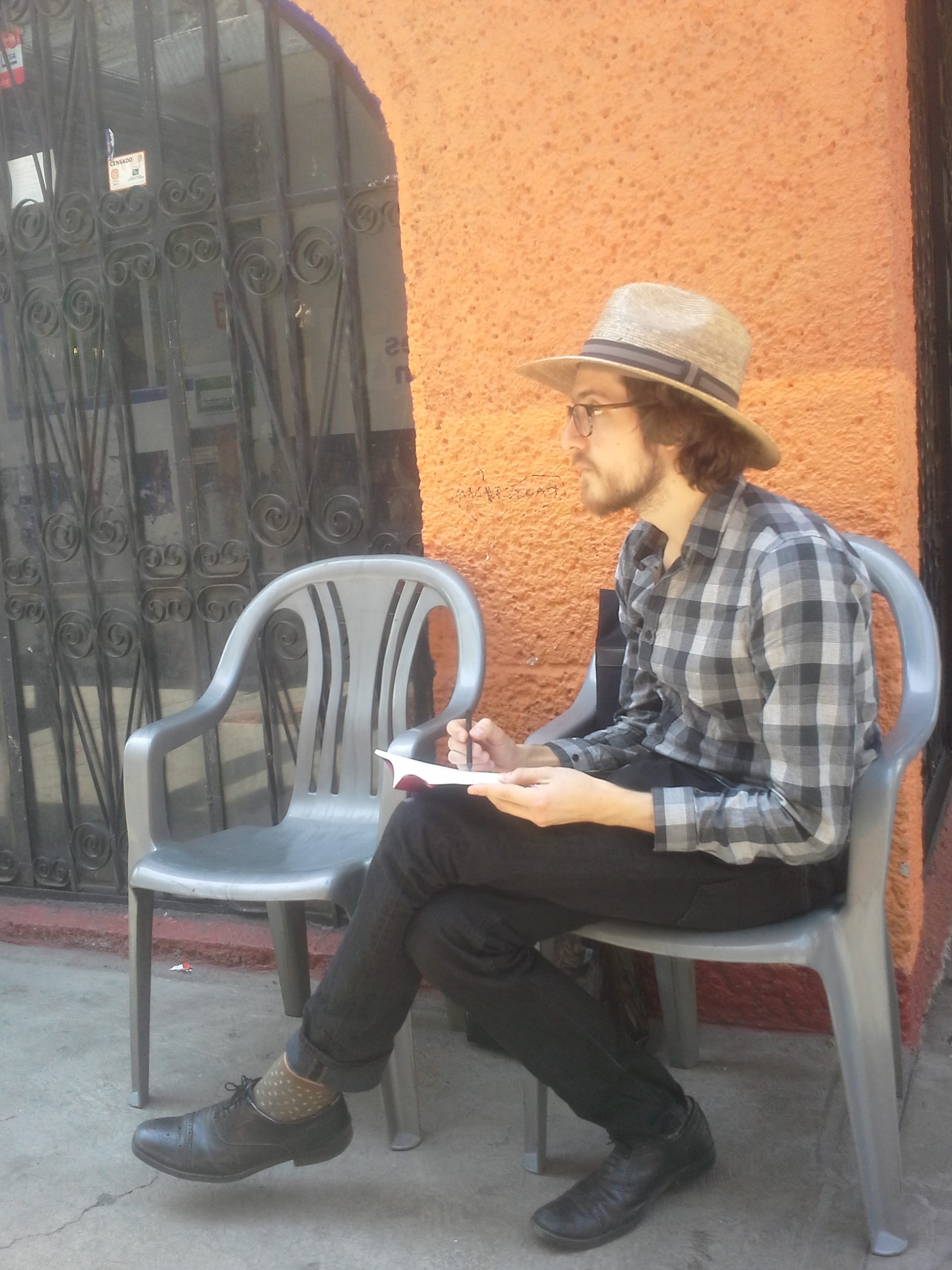

So there I was, in the Jardín de la Bombilla in south-central Mexico City on a hot March afternoon, drawing the cleaning personnel with their medieval straw brooms, dogs, children eating mangoes, the monument towering like the Taj Mahal at the end of the fountains, and stout security guards (the latter have always been my favorite, partially because their expressions never change, but especially because I visit a lot of museums and sketching an on-duty security guard in a well-lit room of Renaissance paintings feels like poking a sedated lion in its own den). Suddenly I noticed that one guard was slowly approaching me. She stopped in front of me and then spoke an order I had never heard in my life:

“Young man, I need to ask you to stop drawing, or leave the park.”

All of the Spanish responses I had been preparing in my head shriveled up, and I had to stare dumbly at her for a moment while I divined something to say.

“What do you mean?” I finally managed, “I’m not doing anything wrong or illegal.”

At this point, according to normal security guard protocol, she would have simply repeated the order, and would have continued repeating it no matter how I protested until her patience ended, leading to the last step which is physical enforcement. However, another astounding thing happened. Rosa (as her nametag said) looked down at my drawings, and her expression softened. She threw the prepared responses out of her head, and told me the following story.

“Listen, do you see that monument there? Do you see “OBREGÓN” written above the door? Do you know who that is? Álvaro Obregón was first a general in the revolution, and then president. He had many famous battles, like against Pancho Villa and the División del Norte, and lost his arm in the war. He was for the separation of church and state, like you have in the United States. But maybe as you know, we are very Catholic in this country, so the resistance to that separation was very strong. On July 17, 1928, Obregón was having lunch in a restaurant that was located exactly in this park, called La Bombilla, when a cartoonist approached him and offered to draw his portrait. The cartoonist’s name was José de León Toral. Obregón saw the beginning sketches and gave the man a seat at his table. When none of the deputies were paying attention, the cartoonist pulled out a pistol and shot Obregón five times in the face. He was executed soon after. Obregón was given a state funeral and this area was made into a park to remember him….”

Rosa had finished the story already some moments ago but I sat in silence. It dawned on me that this harmless act, to her, signaled danger. In fact, it was its harmlessness which made it so insidious, since cartoons are never judged on photo-accuracy (a great retronym) but by the strength of the caricature. I wondered how it had been remembered that the assassin posed specifically as a “cartoonist” (I couldn’t imagine he announced it out loud), but it’s possible that detail wrote itself. José de León Toral used my E-ZPass to gain access to his mark. Since this story was probably as known to Mexicans as the name John Wilkes Booth was to Americans, I suddenly found myself reinterpreting all of the looks I received these past weeks in Mexico City’s parks, cafes, and museums. Were all of those passers-by quietly frightened, but ultimately held silent by common sense or self-disgust? Did their paranoia just seem too far-fetched and disconnected, until this day when I chose to draw in the lion’s den? Was it like the collective rejection of the mosque that was planned down the street from Ground Zero in Manhattan? I had many questions. But the only one I managed was, “Does the drawing of Obregón still exist?”

Rosa’s eyes remained soft. “In fact, yes.”

At my request she wrote the address and directions in a blank corner of my sketchbook. I thanked her, apologized for the disturbance, and got up to leave, before she stopped me and held a page open—the page where I had drawn her some time ago.

“That’s pretty good,” she said. “May I have it?”

I thought for a moment, then said, “15 pesos.”

There was still time in the day to take the metro to Balderas which is directly in front of the Biblioteca de México. I knew where I was going—down the central passageway, left at the Octavio Paz Patio, through the airport-like Galería Abraham Zabludovsky, under its northwest arcade, and into the wooden room housing the personal library of Mexico’s darling writer, Carlos Monsiváis (all places in which I had sat and drawn before). Just inside the room, before passing the front desk, there is an enormous wooden cabinet with a broad display case housing the tip of the iceberg of knickknacks that Monsiváis, a known hoarder, collected. I had only glanced at it before, but that day I stopped for the first time. After a minute of searching, I found it. Still in the original leather sketchbook, held precariously upright and open by an unexplained action figure of a cat, there was the fated sketch. Álvaro Obregón looking out at me from his comfortable dining chair. Or was it him? His clothing was unclearly rendered, lacking any defining marks of a president-elect and former general, the eyes were too narrow, the arms too long… behind him there was no indication of place, only blank paper… his right leg was entirely unfinished, ending at the calf with a hurried twirl, which killed the relationship of figure to ground… there were no tags or descriptions of any individual pieces (partially because there were too many of them)… I thought that if it weren’t for the tip from Rosa, I would never have guessed that this was Obregón at all. I had looked up the president on the way to the library—with his sharp eyes, paunch, hairline, and moustache, doing a good caricature would have been kid’s play. My worst competitive instincts came to the surface, and pulling out my sketchbook I made my own quick cartoon of Obregón (aware of the security guard lurking in the corner) to compare.

So maybe José de León Toral just wasn’t a good artist. Chillingly, this was only 20 years after Adolf Hitler was rejected from the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna. Despite the best efforts of the establishment, it seems bad art manages to creep into the history books one way or another.