Yes, change is good. But wait, no, standards are better. No hang on, we have to let things evolve. On the other hand, consistency and tradition are better values….

Where between these two poles does architecture situate itself? The answer should be: right in the goddamn middle. There should be no noticeable creep to one side or the other, and the profession should maintain a steady adaptability in tandem with certain fundamental principles that we decide are the foundation of the profession, and of nature, as long as the name for it exists.

Notice how I stress the latter? That’s because I’ve noticed an increased amount of “revamps” and “streamlines” and “realignments” that the powers-that-architecture-be are haphazardly imposing on its practitioners. Inasmuch as our words shape our reality, the latest one speaks to a broader crisis of identity.

“…doctors, lawyers, and architects…” This triad, perched on a gleaming tier of the pyramid of professions, has become almost a maxim uttered by admiring citizens. It represents professions that require a lot of knowledge, contain strong codes of ethics, breed responsible individuals and role model citizens, have high prices of admission, are easily dramatized (with the exception of architects), get to wear suits (with the exception of doctors), and can be trusted (with the exception of lawyers). It used to be that simply calling oneself a registered “professional” in any discipline immediately connoted these standards, and it was heavily policed. But the situation has changed– much has been written on the standard of “professionalism” and why it has become diluted and meaningless, with occupations like massage therapy, cosmetology (hairdressing) and interior design (sorry guys) on the official NY State list, and others like bartending in states like NV & TX. Are states capitulating to individuals seeking some kind of special documentation that gives them an edge in the competitive market, or added legal protection? Are the states being too fearful of discrimination? Is there any honesty coming out of this friction, or simply people unwilling to give up rights? The dilution makes sense economically: like currency, if there are more licenses being given out, then the value of each one decreases. But it doesn’t have to be so. The core standards must be upheld, while allowing the total numbers to increase.

Sadly, architecture has felt the effects of this, by association and by Great Recession. As NCARB’s annual report shows, there was a huge post-recession downturn in the number of candidates passing exams and completing training. In response to that, they instituted a series of “streamlines,” which is really a euphemism for “lowering the standards.” This categorized-hours and computerized-examination approach is another step in the search for a lowest common denominator. The irony is that according to that same report, the number of candidates passing the architecture registration hurdles is back on the upswing the past couple of years. So why continue changing the standards?

The crisis of identity crystallized with the latest and strangest step: NCARB’s decision, announced at the 2015 AIA National Convention, to change naming standards for not-yet-architects. They were responding to data that showed discomfort with the term “intern architect.” There will soon no longer be “interns”… but what will we be? The proposal provides no alternative. This is equally good and bad.

Good because:

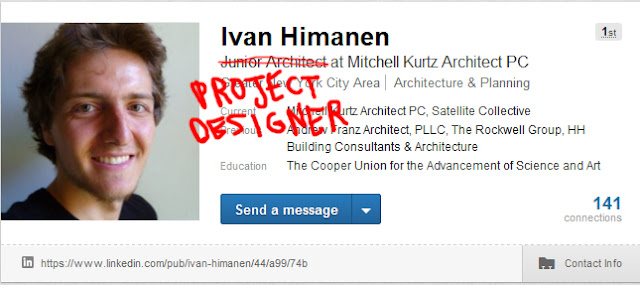

Another irony: very few people in the actual profession use “intern” the same way NCARB does. The term is reserved for only the youngest entry-level employees fresh out of school. Once you begin leading, managing, or designing projects yourself, the name shifts to something like “designer” or “junior architect” or “associate”. And truth be told, even these terms come up seldom– mostly when they’re solicited, like in interviews and resumes. There is also a difference between a business-related job title and a profession-related job title: “partner,” “associate,” “principal,” “staff ___,” or “trainee” reflect your role in the firm from a staffing perspective, while “architect,” or an archaic title like “apprentice” speak more to your standing in the community of professionals. But even these terms bleed into one another. Is a “staff writer” at the New York Times on the same rung as a “staff architect” at SOM? Use of job titles is still mostly a nominal practice, meaning the usage or definition in actual practice is different. And herein lies the crux of the governing bodies’ oversight: they’re disengaged from reality. Allowing actual usage rather than data to shape reality would help us all admit that names are names, but what really matters is the attitude of its bearer.

A slightly related thought: there have been times when the definitions of certain words have decided court cases. Sometimes the court rules in favor of the dictionary definition. But more often than one would think, it sides with the colloquial, more commonly used definition of the word. Lexicon Valley, Slate’s excellent podcast on language, has done such an episode.

Bad because:

NCARB is responding to the fact that most people find the term “intern” to be derogatory, and that it’s unfair to lump fresh trainees with almost-licensed architects working at prestigious firms with a decade of experience who just haven’t passed the Structures exam. But maybe it is fair. At the end of the day, the goal is to make sure architects are becoming Architects not for the name in itself, but for the connotations it bears. We want Registered Architects to be conscientious, responsible, diplomatic, intelligent members of a huge web of other professionals, all collaborating to improve the built environment. And we want the name to truly correspond to those things. We have to work more on strengthening the code of ethics and sense of camaraderie among architects, rather than dilly-dallying with words. My sense is that the best way to keep that standard up is through my peers, not through governing bodies. If I gain licensure at the age of 28 but truly feel unprepared to lead my own projects, I should wait and feel the pressure from colleagues to keep improving until I feel ready. Conversely, if I am 55 years old and cannot legally sign a drawing, I should feel the same pressure every time I call myself an architect.

Noah put it brilliantly: The title “intern” should stay, and stay derogatory, because it’s incentive for people to surpass it.I highly recommend listening to Archinect Sessions’ episode 30. In the episode the hosts travel to the AIA National Convention in Atlanta– and discuss this very decision. Donna Sink and Ken Koense, the token architects of the show, get really into the nitty-gritty and it is an interesting listen. Ken’s calling it “verbal gymnastics” is on point. Donna even suggests calling “interns” “architects” and registered architects “registered architects.” Ken also reminds us that the states individually are responsible for legislating standards, and that the AIA has no power except that of endorsement (hence, why all the hubbub over this naming thing when states haven’t made any moves?)

The discussion starts at 15:20.

This all draws attention to the European standards, which generally set a lower bar in terms of time and money– in fact, a lot of the time you can call yourself an architect immediately upon graduating from an accredited school (there is an exam at the end). With “architect” as a minimum, other titles are added to it or modify it as you gain more and more experience.

Appendix:

I need to fully disclose that I myself am an Intern or Architect In Training, and should be licensed by the end of 2015. But there is also another lifelong architect who is very dear to me who will probably never get licensed in the US. She is my mother.

Through various life circumstances, not least of which include living and working in three countries between the ages of 28 and 35, having a child, and most recently being laid off during the recession, my mother has had to make the most of unforgiving circumstances. Since 2008 she slowly clawed her way back to busybody solvency, and now has established a tiny humming architectural practice renovating townhouses, doing one-off energy and zoning analyses, and has assembled a team of local expeditors, engineers, and registered architects. She works 18 hour days and is happy. She has said she plans never to retire– to work as long as she lives.

Obviously she has completed the required hours, but she never got around to taking the exams. She feels she may never muster the energy to take them. But she doesn’t really need to– she is happy asking someone else to sign the drawings. But the fact bugs her that her Architect of Record, who only reviews the projects and hasn’t designed a single part of them, is taking home 50% of the fees. It is almost silly how someone so dedicated, hardworking, and knowledgeable as my mother is unable to add “RA” to the end of her name (she is, however, a SAFA, or registered architect in Finland…). Her case is marginal, but nonetheless elicits empathy.

I have invented a title for her. It is borrowed from a frequently used term in academic parlance: ABD, or, All-But-Dissertation, describing the final years of a PhD where coursework and required reading are complete, and all that’s left is the darned thesis.

My mother shall be Marina Himanen, ABRA (All-But-Registered-Architect).