Perhaps it begins with the genealogy of the American landscape… the fact that roughly one third of the country’s population streams over beige prairies and terra cotta mesas towards the two coasts, dropping off windward mountain faces to the edge of the oceans… the fact that those 100,000,000 people have formed some of the largest and richest megalopolises in the world… and why those two poles are attracted more to each other than to any other place in the interim… the way they find the opposites in each other, paint portraits of one on the backdrop of the other, then flip it… That is what led me to understand that the way we experience each other and the way we experience our environment is the same.

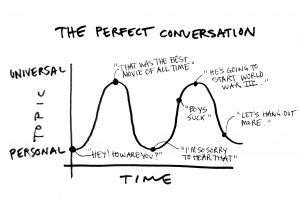

When you, a bred New Yorker, see an old friend from Seattle after a long time, you can’t just talk about your new haircuts or if we saw Mad Max. Nor can you talk exclusively about your new theories on life after your dog died, or about the impending collapse of the capitalist world order. You need to cover both– both the general “how have you been” topics and the specific “did you see that show” topics. And you can’t be abrupt as you move from one to the other– you have to have them morph and bleed into one another, each sentence giving the next more relevance, setting itself up like a good novel. “Did you see Mad Max blah blah blah… but really I think it’s one of the best action movies of all time…. even better than Die Hard, yes. I remember when I first saw Die Hard… It was the day that the transit system shut down because of the third blizzard that winter. Remember?” If you could graph the trends of a conversation over time as it moves between the macro and the micro. A perfectly balanced conversation would look like a sine wave.

Likewise, you relate to your cities as old friends. You are constantly catching up and constantly gossiping, asking what the latest hot spots are while figuring out the future. Since architecture and planning is chiefly a practice of making things that are larger than any one person, you are always on the micro end of these conversations. The city likes to talk about itself, but it also wants to hear what’s new with you. Being friends with your built environment– making acquaintance, hanging out, drifting apart, forgetting each other, then hanging out again– is perhaps the healthiest way to learn from it– because neither it nor you can be reduced to one large-scale or small-scale idea. You both have your own lives to live.

In the summer of 2010, my former professor-turned-mentor Georg Windeck heard that I was visiting Finland and asked a favor of me: to travel to Alvar Aalto’s Experimental House in Muuratsalo and take some photographs of the brickwork for a book he was writing on building construction techniques. I managed the trip by the good grace of my aunt and uncle.

The magic of that house happens by activating the same oscillating dialogue between details and masses, between now and then, between “me” and “you.” The quilt of bonding patterns on the inner courtyard give the visitor plenty to ask the house about (“How many wythes do you have?” “Are your bricks hollow?” “How are you waterproofed?” “How do you sit on the ground?”) while at the same time telling the house about yourself (“My parents lived in a brick house…” “I remember the first night I sat at a fireplace.” “My dream house would look like….”)

Here is Architizer’s coverage of the brick chapter. Read it.