I. Among the Kindies

The AECOM office on 38th and 3rd is bland. Even with the plants, adjustable desks, and breakout spaces, it lacks a certain buzz. The physical traces of creativity, craft, and culture– 3d printed models, vendor brochures, marketing posters, personal knickknacks– are subsumed into the black and white tones of the furniture. For years I thought this aesthetic was merely corporate gentility, the desire to democratically level the playing field for the myriad disciplines and experts our firm houses under one roof. But recently, I discovered it betrays a deeper symptom.

Jennifer and I were sketching ideas for the Toms River Environmental Education Center on a crowded office day at a breakout table. The “kindy table,” as we call it, sits at the confluence of Architecture, Interiors, Project Management & Project Controls, and people on their way to the printer and the bathroom. Every minute someone passed us by. Several stopped at the rustle of tracing paper and peeked with curiosity at what we were doing. Of those, no less than four, some of whom were in leadership positions at our office, said some version of “having fun, huh?” Each time it was uttered with acrid wit, like a clueless father watching his wife and daughter braid each other’s hair.

By the fourth instance I scoffed. What’s wrong with having fun? And why should it be regarded with sarcasm in this professional setting? We were the lead designers for a new social infrastructure project of a size and scope that’s unique for our firm. We were fortunate to take part in it. Instead, through the eyes of the corporation and the busy bees in it, sketching on tracing paper with big markers looked like time inefficiently spent. Eventually, everyone at a publicly traded corporation like AECOM adapts, under duress, the “utilization mindset,” which seeks to make every hour in the office point toward profit. It Excelifies creative professions. Even those who structurally disagree conform to it to survive.

Were this a firm of actuaries, this would be acceptable. But for architects, landscape architects, planners, and engineers, this is repressive. We must bring back fun into our day to day, from leadership to the very cogs that make this company run, we must bake it into the very fibers of what we do and how we work. Otherwise people just show up for the paycheck, and all the talk about “investing in our people” and “embracing quality” remains meaningless babble. I’m picking on my own employer here, but this applies to all architecture and design organizations.

II. Spontaneity vs Totality

Peeling back the onion one layer, I encountered another subtle conflict between having fun and not within the design of the Toms River education center itself.

How do you design a building?

I don’t ask that facetiously. In the collective imagination, architects are artists, who with a flairful stroke of a pen bring buildings to life. But the truth is that most architects are just trying to design the simplest building that checks all the client’s boxes without blowing the budget. Taking into account energy performance, circulation, context, industry standards, and cost leaves little room for creative expression in the traditional sense. Architects’ task is always to satisfy a building’s goals within multiple constraints. Acknowledging this reality, some architects find limitations to be liberating. They turn their whole style and approach into a data visualization exercise– whereby embracing and diagramming the constraints magically reveals the design. When done well, this approach gives the resulting design a sense of inevitability, of optimism as Voltaire would have defined it: everything is the best, most efficient version of itself that it can be, despite indicators to the contrary. And I take issue with that.

I previously wrote on this topic: how some of the world’s most famous contemporary architects who work this way (Bjarke Ingels best-known among them) often let the diagram rule over all, which robs projects of any chance to inject a bit of Mona Lisa-esque inscrutability. While I am no more a fan of architecture which represents the vision of one artist than I am a fan of architecture reducible to its diagram, designing a new building at this point in my life is making me seek opportunities for spontaneity.

Spontaneity is a funny thing. In my lexicon it isn’t synonymous with randomness– a concept I associate more with meaninglessness and cosmic, cold-blooded entropy– it implies a dash of intent, a seeking, the hand of consciousness snatching an object out of a pool of the subconscious. I seek it in art because it is unknowable, it winks at both the rational and irrational and therefore is an open door for contemplation.

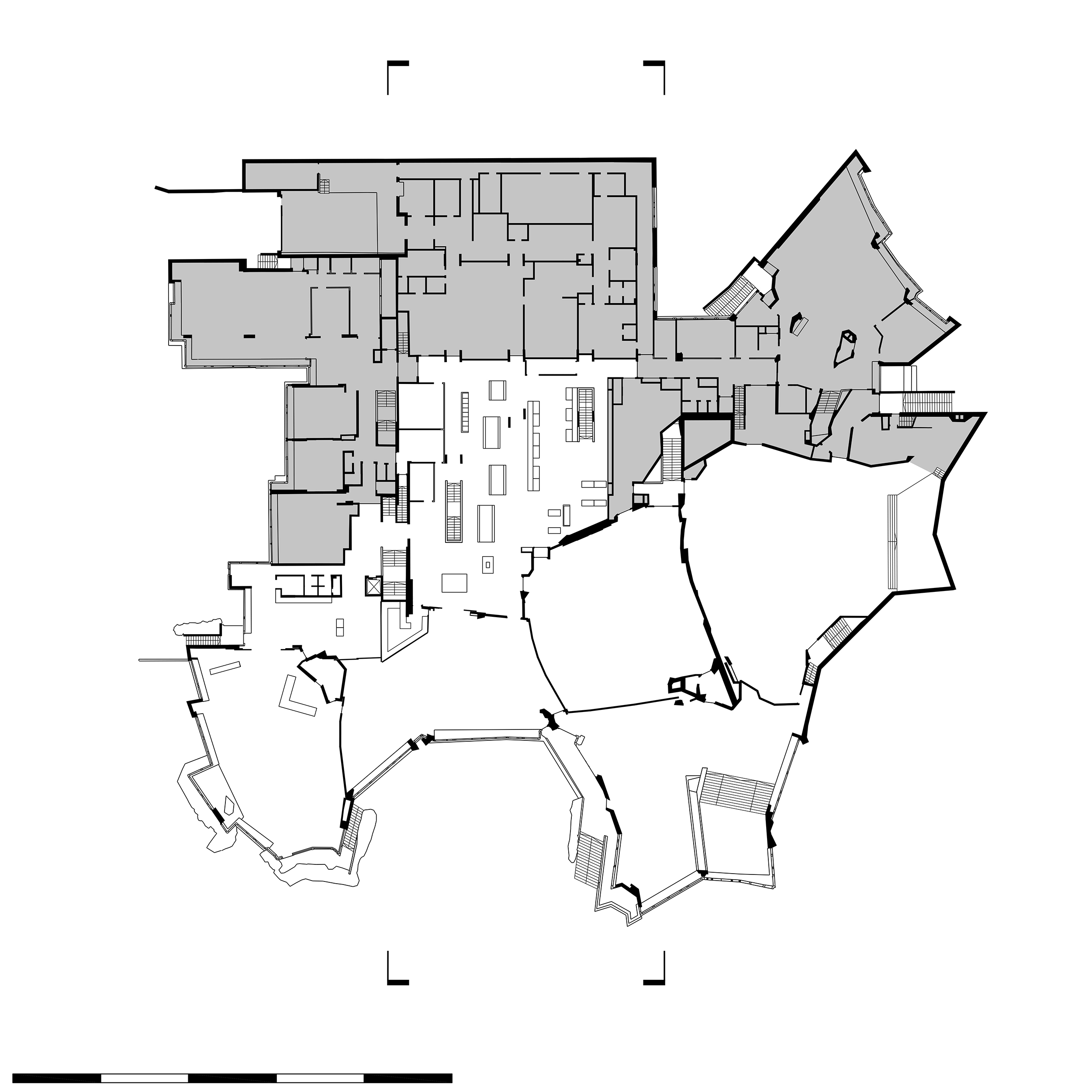

Some of my favorite buildings feature this kind of spontaneity and are the perfect tonic to the BIG-style building-as-diagram. The best example is Dipoli, designed by Reima and Raili Pietilä in 1966, which is now part of Aalto University and sits on the western outskirts of Helsinki. Take a look at the floor plan– there is no equation that generated that geometry.

Compare that with DUO in Singapore by Buro Ole Scheeren. The massing is a one-trick pony: start with two boxes, subtract cylinders from them.

As I move through the world, what keeps my interest more than anything is the possibility of encounter with inscrutable details– phenomena which invite you to look (and think) twice, which are produced by forces beyond your comprehension. Usually those forces are simply other people. People, as behavioral psychologists will tell you, do not behave rationally. They sometimes behave impulsively. The data of our daily lives is filled with “noise.”

I see a parallel here with European football. Over the past decade or so, the biggest teams and the biggest coaches have sought to establish ultimate control over games in order to win. Pep Guardiola, the prime example, deploys a systems approach to the sport, with pitch-perfect tactics and memorized sequences of play which account for every possible contingency and outcome. But football, like architecture, is actually much more spontaneous than we dare to admit, and no one can navigate those ever-changing conditions on the field better than the players themselves. The question is: do players serve coaches? Or coaches players? Recently, a new coaching philosophy in football has taken root and may soon overtake the systems approach– it is, as manager Carlo Ancelotti describes it, “a philosophy without a philosophy.” In other words, give the players only the basic rules, then trust them to make decisions on their own during the course of the game. This leads to moments of creative brilliance which make you jump out of your seat. The Purist Football has put together a brilliant series of videos about the emergence of “football without tactics,” culminating in this video.

Why don’t we adapt this “emergence” for ourselves, dear architects, and call it “architecture without tactics”. From the first sketch all the way to opening day, architecture without tactics is how fun survives.

III. Storytelling

Under the third layer of the onion, we reach a core task of any project: beyond what you create, how do you convey that creation to your clients, your communities and stakeholders, and the world at large? To be worth its salt a project needs a strong story as the engine. And a strong story is not something tacked on post factum– it is crafted throughout, woven with the filaments of fact, imagination, and agency (that is: a desire to shape one’s future), and it penetrates the process, fitting into every breathing space, holding the pieces together with astonishing, Velcro-like tenacity.

Being creative acts, stories struggle to survive in big corporations. A story that sacrifices factual precision (not accuracy– I’m not advocating lying, I’m advocating gloss) for a compelling or unique take on reality is often deemed too risky to deploy in a high-stakes project. Because they aren’t easily reducible to a checkbox, they get devalued. Ironically, the time a good story can have the biggest impact is in the beginning of such an undertaking, when a client is only just picking a designer and deciding the size of their purse. Successful RFP responses, for example, don’t waste time digging into technical details, instead tickling the prospective client’s imagination with optimistic visions of what could be.

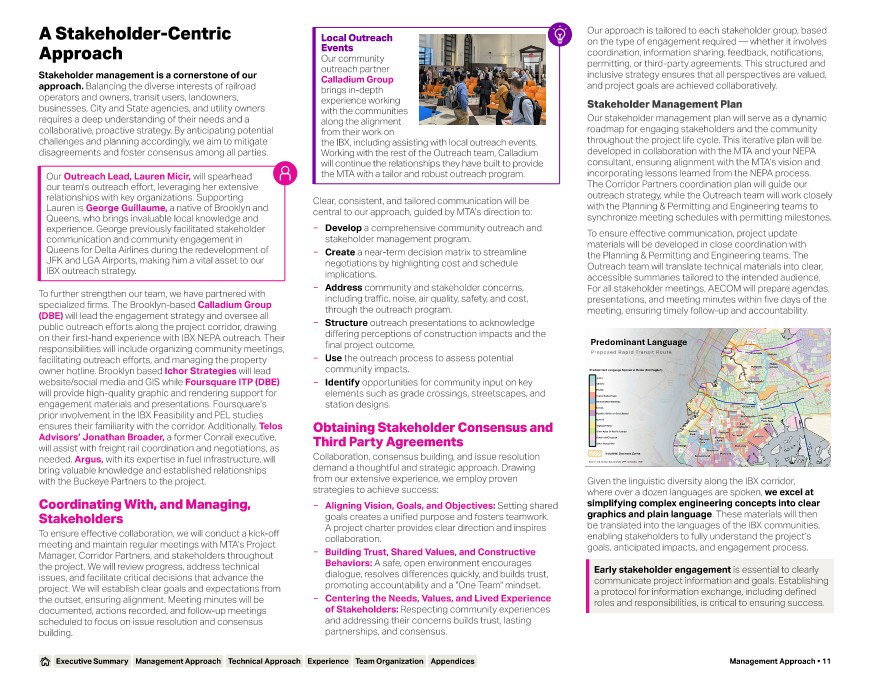

Below is an example of a typical page AECOM put together in our response to the MTA’s RFP seeking a lead program manager for the Interborough Express light rail system, or IBX.

It doesn’t take Roman Mars to tell you the problem. Too much text, not enough imagery. Too much jargon, not enough filament. Too much fact, not enough gloss. Visually, it’s oatmeal. No wonder we didn’t win.

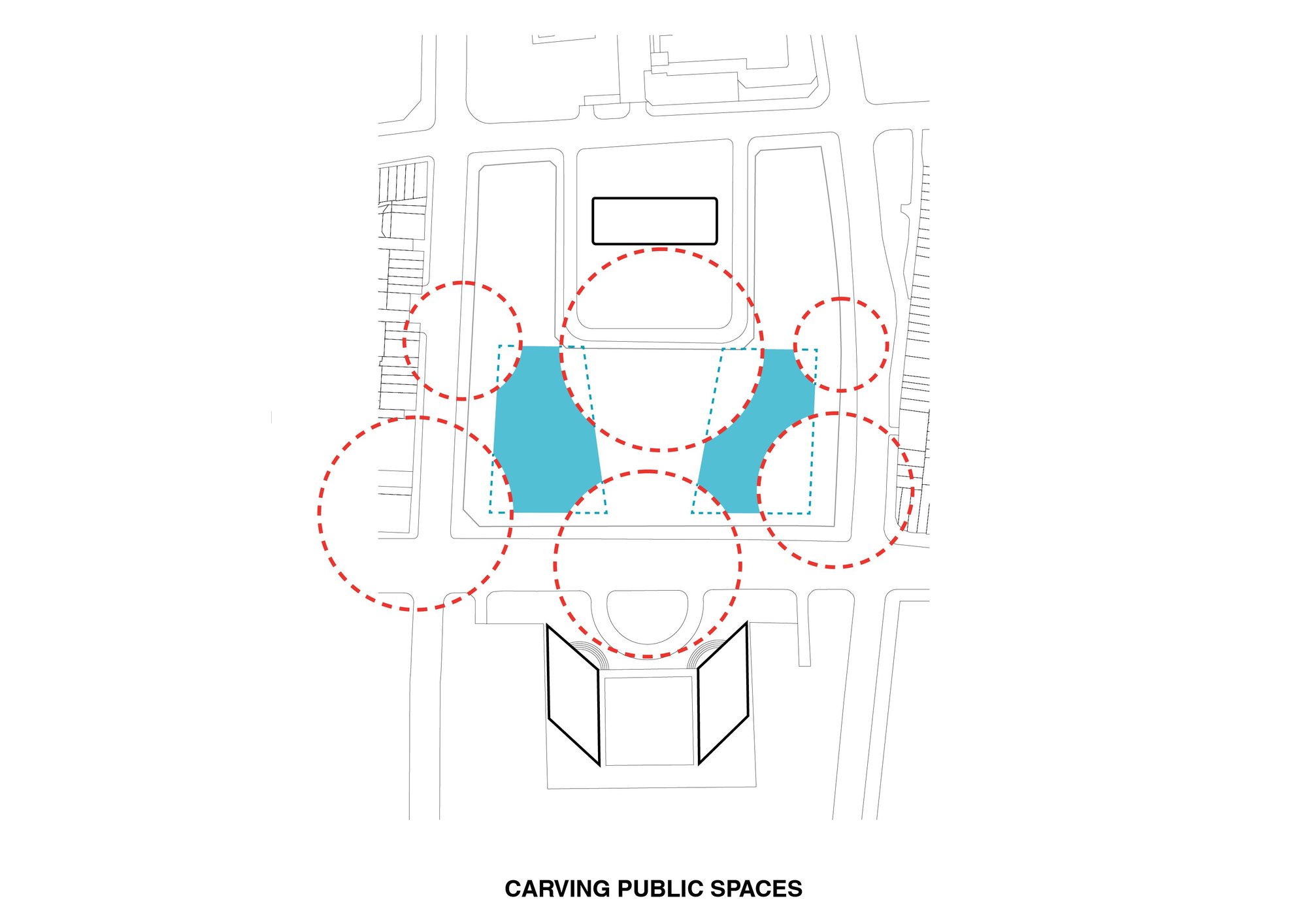

I was on the team producing a few diagrams for that proposal. Within very tight spatial limits, we had to be as concise and legible as possible. I proposed a cartoonish visual palette, with primary colors, silhouettes, and word bubbles (an example below). However, the technocrats within us feared leaving boxes unchecked, and the images evolved into premature renderings. The magic was sapped.

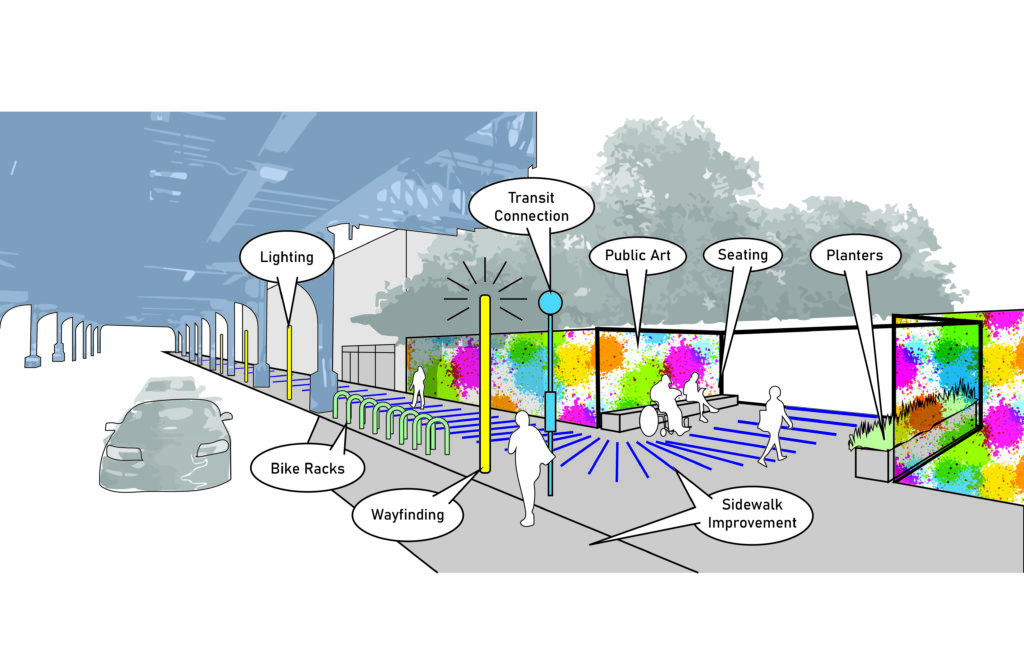

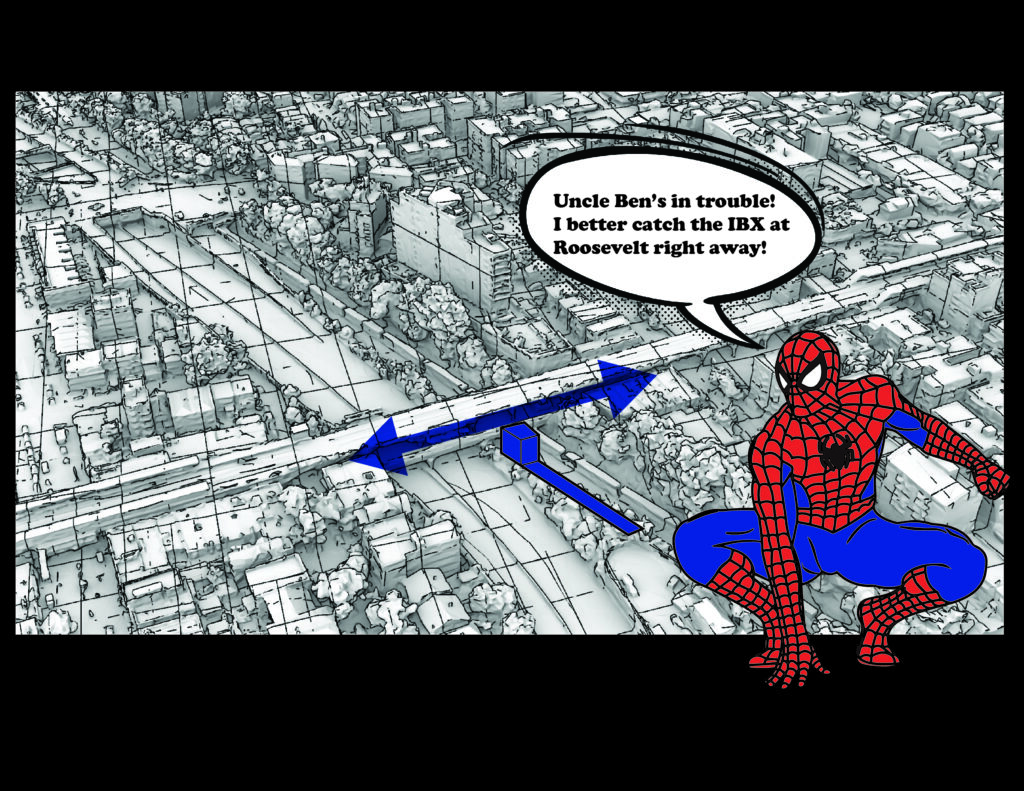

My moment of brilliance came while fiddling with display styles of a Rhino 3D model of the Roosevelt Avenue Station context. The buildings and streets we scraped from the internet came as a mesh divided into squares, and turning on ambient shading as well as edge silhouettes gave me an effect that strongly resembled a vintage comic book. My mind immediately ran ahead. Comic books… New York… wasn’t Spider Man a kid from Queens? Wouldn’t he be one of the ideal riders on the IBX, traveling crosstown from Jackson Heights to the Brooklyn Army Terminal? I mocked up the following image.

OK, Spidey himself is occupying a third of the image, but who cares? The caption says it all. We get Brooklyn and Queens. We know the importance of transit in New Yorkers’ lives, how catching the train just as the doors close can make you feel like a superhero. Mostly importantly, we know how to have fun while delivering an impactful and technically demanding project, which means we know the importance of loosening our professional straitjackets in order to listen to those whom this project impacts.

Having fun, like storytelling, interweaves the filaments common to all of us as citizens so that we all see a piece of ourselves in the end result. We agree upon the same rules before embarking on a game of freeze tag. Such is the eternal task of architecture– making the “frozen music” feel like something we have all tagged on its way.