I: A Semi In A Strange Land

These days, Charlotte and I hardly need alarm clocks to wake up in time for our morning walks. Around 7:30 in the morning, three things come to life in the neighborhood which rouse us: first, the robins and mockingbirds ramp up their chatter which flows in through our bedroom windows; second, our upstairs neighbor’s daughter commences her own morning exercises of sprinting back and forth along the apartment’s 40 feet of hallway, thumping along the aging floor planks; and third, the trucks arrive at Key Food Supermarket across the street and begin their mechanized chorus, idling baritones, car horn tenors, and back-up beeper sopranos. Drowsy but optimistic, we exit onto Montague Street. Morning walks fulfill multiple objectives: upholding triscuit-thin but vital relations with the local shopkeepers (Ali at the Corner Deli and Sam at the Pet Emporium); reminding our eyes of the awesome skyline across the East River; kick-starting the flow of blood to our extremities; coaxing the kind of morning hunger which makes the stomach feel like a stretched rubber band; and giving us the lay of the land, the state of the streets, like barons atop a hill surveying faraway vales.

These walks carry a consistent mood: the sense that things are under control, that the untamed darkness is giving way to the rhythms of daylight. It is like the giddy feeling when the house lights dim before a concert, only here the lights are coming on. Every object in the neighborhood is in harmony and on schedule.

But, once in a rare while, we happen upon scenes whose parts do not quite belong together, where the rhythm is syncopated or totally irrational. Even in a city as up-for-anything as New York, these scenes stand out. Some of them are amusing (a homeless person giving directions to a drag queen at a Gray’s Papaya), some are saddening (an entire set of discarded bedroom furniture, made-up bed and all, on the sidewalk), some are disgusting (a pigeon eating a chicken wing outside KFC), and some of them are infuriating because they obviously stem from poor planning. This latter is exactly what we experienced one morning.

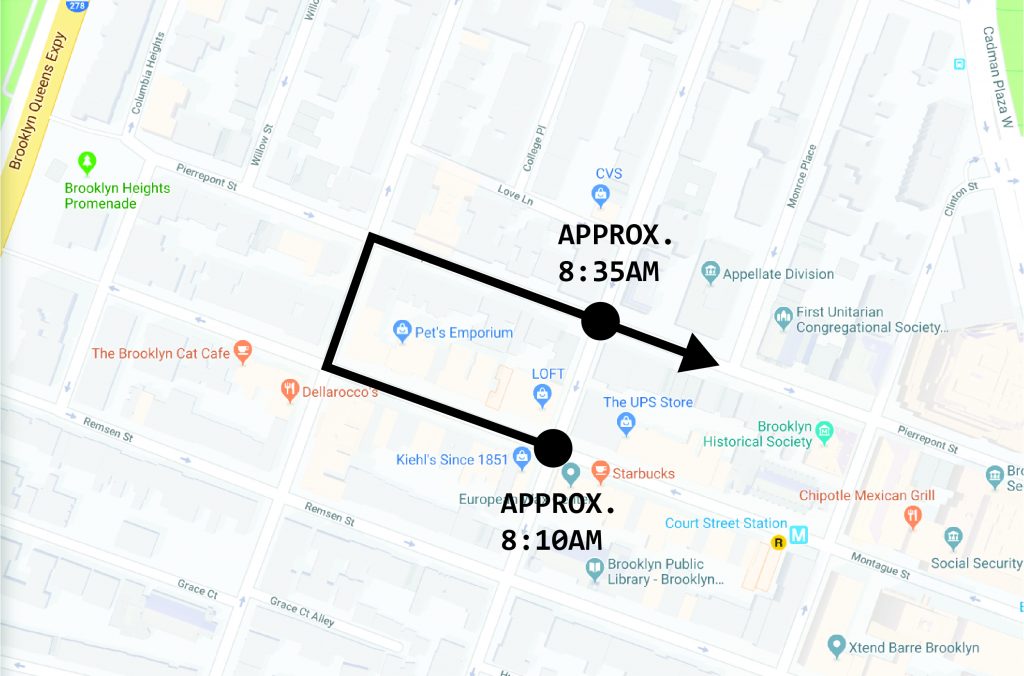

At the intersection of Montague Street and Henry Street, a 50-odd-foot-long semi-trailer truck with a Western Express logo was idling at a 45-degree angle. It was obviously in the middle of a turn from Henry onto Montague. Traffic stretched one block back along both streets. Part of the trailer was overlapping the sidewalk corner. Pedestrians were congregating at the intersection to watch the driver make his maneuvers. We stopped to watch too. The turn required about 10 points, each back-and-forth requiring an adjacent parked car to move out of the way. Miraculously, the only property that it damaged was a knocked-over plastic Gay City newspaper box. Once the truck cleared the last car and straightened out onto Montague, everyone sighed in relief. Someone applauded. Charlotte and I walked on, muttering in awe.

We the living respond intuitively to mismatches of scale, like when such high-capacity machines borne of warehouses and highways enter low-capacity residential spaces borne of flowerbeds and baby strollers. The tension is palpable. The inquiries of passers-by, even those muttered to oneself out of curiosity, take on the legal tone of a concerned citizen, or the existential hopelessness of a war refugee.

How did that semi end up there?

Presumably, it was there to make a delivery. But aren’t local logistics usually restricted to much smaller trucks, like the ones that normally wake us up in the morning? Semis, such as this one from Western Express, deliver large volumes of goods from storage point to storage point, inhabiting almost exclusively the exurban landscape of warehouses, parking lots, and major arterial roadways (there’s a reason those places don’t have sidewalks). If it were in front of the Trader Joe’s on Atlantic Avenue and Court Street, then I’d understand. Something was amiss in the complex grocery supply chain.

One force which may be behind this unusual incident is demand-side pressure on the market. Since Amazon Prime, we consumers have gotten accustomed to near-instant, on-demand delivery of goods, no matter what the cost. Those costs are often borne by the delivery and logistics companies such as Amazon itself and Western Express, who use up extra cardboard and bubble wrap and gasoline in order to fulfill our orders as soon as possible. One common side effect of this, which has snuck up on us, is piles of cardboard boxes cluttering apartment building lobbies. It’s possible that the Key Food on Montague was missing a critical item after the morning delivery, and demanded to be made whole. It’s possible that the Bossert Hotel (undergoing condo renovation) or the new Cat Cafe (further down the block) is being managed by a novice who placed a separate order for a few pieces of furniture. It’s easy for city dwellers to scoff at truck drivers. But they are just messengers. It may be that city dwellers themselves are asking for too much too quickly.

II: A Zero-Sum Game

Vehicles and pedestrians have been at odds since the first civilizations. Cities, from Sumer to New York, are places of congregation, where many people and many resources come together to increase wealth and prosperity. Those people and resources are brought in from outside in large volumes. Once they arrive, though, the idea is to disperse them as quickly as possible to make room for the aforementioned prosperity. This makes sense: a city needs space for office buildings, parks, sidewalks, housing, and all of the other stuff that transform the steel, produce, water, and tourists that it receives into economic activity, leisure, consumption, et cetera.

As cities continue to densify, and available territory becomes squeezed, this conflict between vehicles and pedestrians has become a zero-sum game: one side’s gain is the other side’s loss. This is illustrated with geometric clarity in the distinctive chamfered corners of Barcelona’s city blocks. Ildefons Cerdà, the engineer behind the 1850s master plan, foresaw a city in which even small neighborhood streets are boulevard-like, with grandiose intersections and freely-flowing traffic. Cutting off the corners of sidewalks and buildings as Cerdà did makes it easier for traffic to turn, a critical detail given how the mobility landscape was about to change. Horse-drawn carriages were still the prime method of medium-distance traveling in cities in the mid-19th century, but a working adult at the time would have lived long enough to witness the advent of the motor vehicle. Ironically, those corners are nowadays mostly occupied by parked cars and scooters, so the sensation of freely-flowing traffic has been dampened. Nevertheless, those 125-square foot triangles are real estate that was taken from pedestrians and given to automobiles.

The next great automobile expansion after World War II, spearheaded by Robert Moses and the public works projects of the post-Great Depression years, was fueled by the same vision as was Cerdà 80 years before: that boulevard-like streets, grandiose intersections, and freely-flowing traffic are indicators of a healthy city. Of course, we have learned quickly that being in cars all day is not the end-all be-all of desirable lifestyles, and that all of the space that highways occupy is space that is taken away from pedestrians and smaller-scale neighborhoods. This problem is especially acute along waterfronts, where people are streaming to nowadays, but which in many cities are blockaded by motorways. The Brooklyn Heights Promenade was created specifically to combat that inaccessibility.

The Brooklyn Heights Promenade is a pedestrian path overhanging a two-tiered Brooklyn-Queens Expressway and a service road at grade, all cantilevered out of the rock underpinning Brooklyn Heights itself, and overlooking Lower Manhattan and New York Harbor. This stack is like the Big Mac of mobility infrastructure, and it continues to be a fan favorite for both cars and for pedestrians. However, that piece of infrastructure is now nearing the end of its life, and serious steps need to be taken to fix the motorway, preserve the promenade, or rethink the entire setup. Whatever the outcome, the spaces and flows currently enjoyed by both pedestrians and cars will be disrupted. The debate rages, the tug-of-war is on.

One of the points frequently made by enemies of the BQE in general is that any long-term construction on the highway would forcibly divert traffic onto local streets. And while traffic engineers have yet to confirm that this will actually happen (for similar but inverse reasons why building wider roads does NOT relieve congestion), it follows the zero-sum-game narrative, and residents respond strongly to it. The thought of a semi huffing and puffing through the 50-foot-wide streets of Brooklyn Heights gives many people nightmares. Interestingly, the Western Express incident was most likely caused by entirely different forces. But its coincidence with the BQE debate may, entirely by accident, give people a sneak peek of a false future.

Coda

Charlotte and I returned from our walk 20 minutes later, and we saw the same truck heading east on Pierrepont & Henry. So it had made three right turns on three consecutive intersections! What was it doing? I emailed Western Express to find out. No response yet. This investigation will have to be revisited.