The following is an excerpt from Building Sights, a BBC TV series which features famous works of architecture around Europe and the US– and the architects, artists, writers, and celebrities who provide short essays describing them.

The parallels struck me immediately. Replace “Glasgow School of Art” with “Cooper Union” in Bruce McLean’s essay, and the text becomes instantly contemporary. Think what you may about Morphosis’ NAB @ 41 Cooper Square, the questions raised in the last passages affect us all. I’ve added color for emphasis.

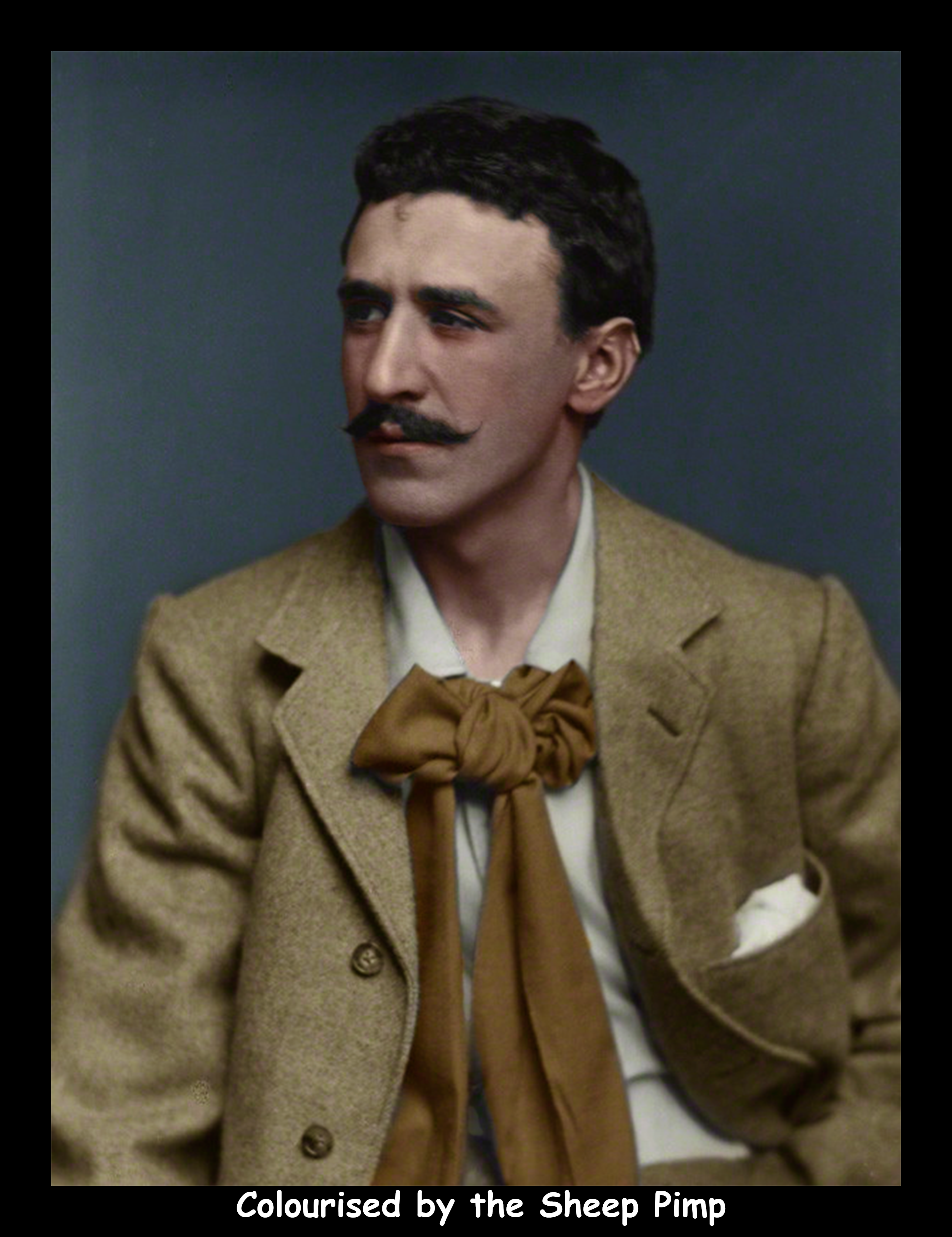

“This is one of the great modern buildings that set the pace for the twentieth century and I don’t think we have kept up with it. The Glasgow School of Art was designed by Charles Rennie Mackintosh. An artist couldn’t have a better start than to study at the Glasgow School of Art. I’m certain that the reason I have worked with so many different materials– paint, stone, film and ceramics– lies here at this school. Mackintosh was a master of many materials: iron, wood, bricks, mortar, glass, concrete, tiles, fabric, upholstery and even hair– look at his moustache, it’s practically a piece of sculpture.

“The beauty of this building is that Mackintosh makes the parts add up. There’s a grand design inside and out, and I don’t just mean the outside walls, I mean within the rest of Glasgow, because unique as this building is, it’s very much part of the town. You can’t imagine another building sitting on that slope. From where it squats you can build up a composite picture of Glasgow.

“It is a physical building. It confronts the world putting on a different face for all four points of the compass. It is outward-going, but never aggressive. It is an optimistic building, it has to be because of its function– to foster the creation of art. Art shouldn’t be about hiding away in a corner and whingeing with angst in your pants– it’s about facing the world.

“There’s something vigorous and Scottish about the building and you can see how Mackintosh has used traditional native design. Yet his genius lay in the assimilation of other influences of the Japanese, and Art Nouveau. From one angle the building has a foot in the baronial Middle Ages, from another a foot in the twentieth-century.

“It was put together with a purposeful defiance of the law of symmetry. However, this asymmetry doesn’t stop the building being a homogenous or living entity. There is an organic logic to the building. The corridors and stairwells bring the masterplan to life, forming all sorts of interconnections on different storeys. You are kept on the move– in spirit anyway.

“It is a young person’s building not because Mackintosh was barely in his thirties when he built it but because of the spirit. You don’t get anything like it today. This isn’t nostalgia on my part, a case of older being better, it is a case of people only building to apologize or conceal. We are afraid of being Modern so we Post-Modernise, and these Post-Modern buildings make us feel worse, not better. So in today’s climate the Mackintosh building stands out– a Utopan beacon. The pity is, Mackintosh was hardly allowed to build anything in his day. He was ahead of his time and we are only just catching up with him or are we?

“Nowadays when art education is being dismantled, and education seems to have fewer resources, it has become more difficult to match Mackintosh’s optimistic vision: we lose sight of it at our peril.”

Bruce McLean’s bio @ Tate’s website.

Lastly, given GSA’s recent awful luck after its library was heavily damaged in a fire, we hope it will find an appropriate, inspiring solution for restoring its architecture and functionality.