Yarn I:

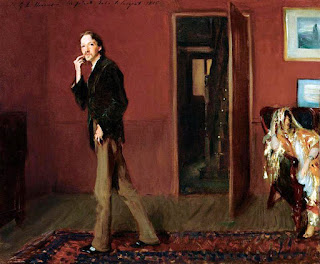

It seems one of the primary artistic trends of the 20th century (with spillover, maybe the last two centuries) was the increased acceptance of sketches and raw, undeveloped ideas as legitimate “works of art” ripe for an audience. The beginning of the last millennium would not have indicated this, though– the market and prevailing aesthetic became awfully formalized and refined, to clientele richer and to art with corresponding burdens of grandeur. Art was occupied with things entirely other than presenting an idea. Most of it was advertisement and record-keeping for posterity. Here we have some Medicis, history’s greatest accountants.

A large portion of art was also used by the church to convey extant episodes of morality and ethics in the grand story of Christ et al. There seemed to be stricter rules, or at least expectations, in place about the conception and reception of artwork. Slowly that formality has eroded and now an artist can display almost anything, and almost nothing– a single line, an empty frame, a person standing still– to an audience, giving the latter more interpretive work to do.

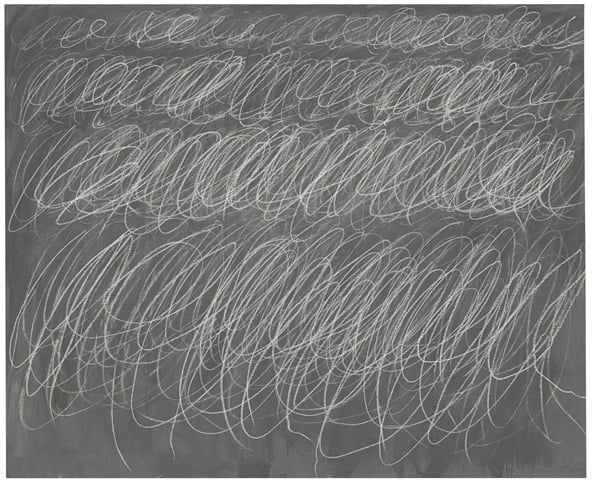

Or so you’d think. Because instead of compensating for new forms by expanding its visual vocabulary, the audience has duly complied with the artists’ lead and become lazy at its end. Nowadays, the simpler a piece looks to the average gaze, the more likely it is to need explanation– and hence, justification. It’s obvious that if an artwork needs excessive analysis and explanation by experts on behalf of the masses, then you have a problem.

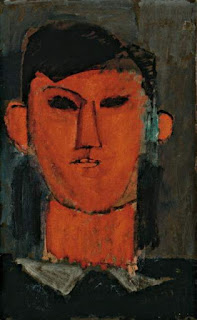

Perhaps this all conceals another truth: that what we call art has in fact changed its scope of services to society entirely in the past millennium. Before, it served even the poorest churchgoer, with strong, understandable language of form as its base, and practicality and relevance as its engine for communication. Since then, the art world has dwindled to serve, and with decisively less practicality, the intellectual accumulation of a select few.* In a way, though, this has given painters and sculptors the freedom and the license to conceive of almost anything, trying always to break that next ceiling in the endless skyscraper of taboo. The first steps of that: adoration of the sketch, and the slow and ultimately successful creep towards accepting things in a raw and newborn state. Here is a rough visual timeline, from the 1850s on:

You could read many things from this trend, such as the effects of war on mankind. But I am presenting these simply as visuals, as images experienced here and now.

Yarn II:

With rawness now accepted pretty much as a style, it has begun translating into our daily lives. The artist’s sketch does two things for us: 1) it evokes those emotional responses that art is so good at doing, and better that something overly worked-on (and potentially heavy-handed) and 2) inspires us to say “my kid could paint that. Heck, I could paint that!” Steadily, it seems technology has given us just that ability. We are now given the option of entering a constant stream of auto-biography, with every next piece of technology promising things delivered in “real-time.” Compared to earlier when I had to wait months to get a book published, I can now type a little and click a little and have my book online and available to anyone within one night. With Twitter, I’m not even confined to my laptop anymore. There is increasing legitimacy given to the most mundane musings. Check out Conan’s Twitter feed.

Now before I make my next statement, picture language (that is: English etc.) abstractly, as nothing more than a tool or mechanism for communicating ideas. Like smartphones, it is a brilliant thing. But also like smartphones, it is imperfect. There are some ideas that the English vocabulary somehow cannot grasp, and on top of that, think of how laborious it is: before the person across from you understands your thought, you have to figure out what to communicate, communicate it, then they have to receive that sound (pretend you are just talking with no visuals– on the phone, for example) and process it themselves. On average this transaction takes roughly 2-5 seconds. Quite inefficient, isn’t it? Why that second processing phase? And isn’t there a way to actually make communication real-time? That is, I don’t have to find equivalents in the realm of words and gestures to convey my thought– I can literally put that thought in an interlocutor’s head.

Well, herein I make my prediction (which is extrapolated to occur sometime in the 100th millennium (100,000 AD): imagine moment in our evolution when we reach some level when we are able to communicate our thoughts to each other purely and instantaneously. In a way, it won’t be communication at all, because communication implies that primitive slog of processing and gesturing and so on. It will be more like us floating in an ether: an ether that receives a thought from one person in it and which would instantly be understood by everyone else in the soup. To get a feel for it, try thinking of something, then communicating it to yourself. You see, the need for communication is gone, because you had that thought in your mind already. It is maybe very similar to Nirvana. This, I envision, is going to be a huge step in the evolution of man. But that’s obvious, because you must have already concluded that. (Case in point?)

*Evidence: those de Koonings at MoMA (hanging for the benefit of the public). The reason they are up there is not because the public immediately got their underlying message 50 years ago, but because some highly reputable individuals did, and explained it to us, upon hearing which we collectively uttered “Ooooooooh…”

Furthermore, their intimacy is leagues separated from shock art featuring Jesus and heads of state, and encroaching on that feels completely at odds with their white-box homes. These paintings might belong in the studio.

:this, not this:

Though its schism from the church was a good thing in my opinion, there is one thing from that time that is missed in fine art: its ability to communicate powerful messages, cheaply and quickly, to and for the benefit of many. I guess film & television now hold those reigns.